16 May

2012

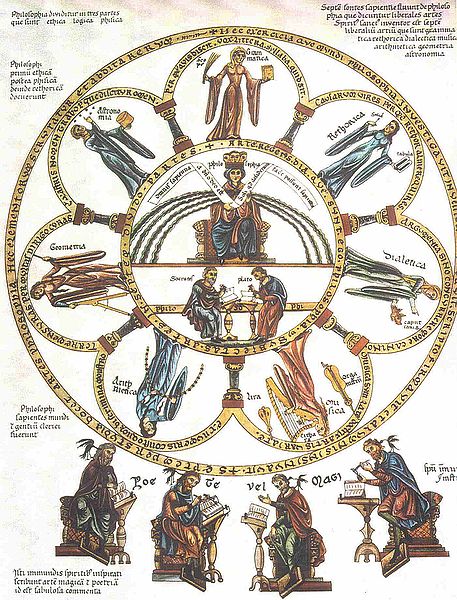

The Liberal Arts, A.C. Grayling and the Catholic Church

Posted in Education, Philosophy

The New College of Humanities is a recently established academic institution based in London. It is the project of well-known academics such as A.C. Grayling and Richard Dawkins. Students, alongside their chosen degree, will be required to study a few core modules emulating the liberal arts method of many North American colleges. A number of individuals within academia have criticised the project as potentially elitist and most definitely a bad imitation of Oxbridge. The College appears to be set on opening according to schedule with a first group of students enrolling in September.

There is also a proposal at present to establish a quite distinct privately-run college teaching to a liberal arts curriculum. This is a project of Catholic academics and professional people, and it will be called Benedictus. Unlike at New College students will all follow the same course which will cover a range disciplines including those of theology, philosophy and mathematics.

It might be argued that the appearance on the British scene of two colleges offering a liberal arts curriculum builds on perceived dissatisfaction with the existing system of higher education. Some argue that it is too specialised and does not fully form students in intellectual curiosity and in a deep appreciation of knowledge. Arising out of not dissimilar concerns, there has been for some time a move, within secondary schools, both state and independent, towards the International Baccalaureate.

The ideological differences between the two projected colleges are, on the face of it, considerable. New College is the creation of leading atheists while Benedictus is the work of committed Catholics. There should be no surprise here. University College London (‘the Godless College of Gower Street’) was established early in the ninetenth century by people who felt religion should not determine the policies and ethos of a university. King’s College London, partly by way of reaction to the creation of UCL, was set up by a body of committed Anglicans. Whatever their foundational impetus and special interests, academic institutions must, if they are to be credible, ensure a measure of objectivity and openness in their teaching.

In the case of Benedictus the proposed curriculum seems fairly balanced. If it includes study of works by Aristotle, Aquinas and Scruton, it also offers Hume, Nietzsche and Sartre. The literature for the College makes it clear that students will be encouraged to develop their ability to assess and analyse ideas critically.

The literature for New College gives no such detailed syllabus, yet it seems clear from the academics employed and course titles offered that balance is unlikely. Those engaged in the philosophy department are well-known in part at least for their ardent atheism. The language used in the literature mirrors that used by the academics in dismissing the reasonableness of faith. One course listed is Philosophy of Religion. It can only be hoped that the course will be taught with balance and objectivity, allowing scope for reasoned arguments in defence of religious faith alongside atheistic critiques. It would be sad if only the straw-man arguments beloved by Prof. Dawkins were provided. Again, we can only hope for such balance when students take the core subject of Applied Ethics.

A healthy system of higher education will, besides insisting on academic rigour and integrity, remain open to serious competition. If two new liberal arts colleges demonstrate such qualities, a valuable contribution may be made to British higher education. Other institutions may enter the market if they are successful and balanced. It is even possible that the new ventures will push existing institutions to offer a broader and richer academic education.

Leave a Reply