Published on

25 April 2007

Postcommunism and Constitutional Democracy: The Case of the Czech Republic

By: Dr. Ludek Rychetnik— 2006-2007

ABOUT

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik is Lecturer at the Institute of Economics in the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, Prague, and at the University of Reading Seminar on Wednesday 25 April 2007

In the heart of Europe, the troubled world of Franz Kafka seems to be gaining ground over the hopeful world of Vaclav Havel. The historic cities of Prague, Warsaw, Bratislava and Budapest look impressive enough, but economic progress is increasingly overshadowed by political turmoil.

Charles Gati and Heather Conley: ‘Backsliding in Central Europe’, International Herald Tribune, April 3, 2007

According to the system of natural liberty, the Sovereign has only three duties to attend to:

first, the duty to protect society from violence and invasion by other independent societies;

second, the duty of protecting, as far as possible, every member of society from injustice or oppression by any other member, and the duty to establish a system for administering justice;

third, the duty to create and maintain public works and institutions, which are for the public benefit and not of the individual, or minority, as the profits from such enterprises can never repay the outlay of any individual or group, though the advantages resulting from such public institutions may well do more than repay the costs to society in general.

(Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776, Book IV, Chapter IX)

1 The problem

When Andrew asked me to prepare this paper three months ago he must have been in a prophetic mood. Central Europe has become ‘interesting’ since then.

When Andrew asked me to prepare this paper three months ago he must have been in a prophetic mood. Central Europe has become ‘interesting’ since then.

The quotations above introduce my paper and also describe my background: the first quotation introduces the problem. The second suggests the causes.

Amongst other things, I will talk about the role of government in post-Communist societies and look at how economists are renewing their lost understanding of that role. Mostly I will talk about the Czech Republic and only mention other Visegrad Countries and the UK by way of comparison.

In the first and longer part of the paper I will try to give a picture of the post-Communist soul in terms of data about culture, understood as generally shared values, beliefs, and attitudes, hidden assumptions and ways of thinking about social life and politics. I will argue that post-Communist political culture has not been able to create a historically stable liberal democracy, in the sense of a regime of ordered liberty. In the second, much shorter part I will formulate a seemingly obvious solution: aiming to ‘amend’ political culture and I will ask you for ideas. If there is still time I may mention some initiatives which have arisen for that purpose.

With regard to my identity, I aspire to be a political economist covering the range of Adam Smith’s interests. He was a moral philosopher, looking at the social world in its widest dimension. He was aware that a limited view is not enough. In the quotation Adam Smith refers to the system of natural liberty and to the maximum the Government should do within the system. But at the same time he lists the necessary functions the Government should perform. Without them there can be no civilised society and no economy can work properly.

Speaking about the loss of understanding by economists, I refer to a set of reform recommendations, known under the name of ‘Washington Consensus’. This was the official World Bank and IMF advice package given to Latin American countries in the 1980s and to post-Communist countries in the 1990s. They were no doubt healthy economic principles: to adhere to strict monetary and budgetary discipline, to privatise state firms, to deregulate prices and foreign trade and rely on the free market and its ‘hidden hand’.

However these recommendations took for granted a consistent fulfilment of the three duties of the sovereign, as spelled out by Adam Smith. But they could not be taken for granted in Central and Eastern Europe after the breakdown of Communist rule in 1989 and the 1990s, with poor or non-existent legal regulation of the economy, inefficient protection of property rights, and unreliable enforcement of contracts. The failure of the sovereign’s role in these basic duties resulted in chaos, arbitrariness and plunder by the powerful, rather than the free market. Only in the late 1990s did some economists realise what was going on in the so called ‘countries of transition’.

A working paper of the World Bank in 2000 has a characteristic title:Seize the State, Seize the Day: State Capture, Corruption and Influence in Transition. (‘State capture’ means that powerful groups capture the state and use it for their own enrichment.) Yeltsin’s Russia provided an opportunity for, and demonstration of, this (see, e.g., Jeffrey D. Sachs and Katharina Pistor, The Rule of Law and Economic Reform in Russia, 1997, or J. E. Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents, 2003). Joseph Stiglitz as the chief economist of the World Bank, and James D. Wolfensohn, its 1995-2005 president, were instrumental in refocusing its attention on good governance and anti-corruption programmes as being central to its task of alleviating poverty in the late 1990s. [www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance].

Fortunately, because the basic rule of law had deeper roots in Central Europe, things did not go as badly wrong there as in Russia.

2 Economy and Polity – the State of Affairs

What is the situation in the Czech Republic and other Visegrad Countries?

(i) The economy is doing reasonably well and most people seem to be happy with their standard of living.

Graphs: Economic Situation of the Czech Republic and Other Visegrad Countries

The approach to economic inequality and poverty differs from country to country, the Czechs being the most sensitive to it and reasonably successful in controlling it (a practical Christian virtue of an otherwise largely agnostic nation?).

(ii) Politics

People are generally not satisfied with how the country has been governed. Personal trust in governance is low.

It is not surprising that people do not trust the Courts of Law and are not satisfied with their performance in the Czech Republic. In 2005 the average duration of a business case was 1380 days. Bankruptcy cases took 1876 days and sales contract cases took 2020 days on average (Ministry of Justice).

Table 2 continued: Czech National Pride

The items held in high esteem (in the lower part of the table) indicate the sections of social life where people recognise natural elites they are proud of. Natural elites do not seem to flourish in politics, administration or the economy.

3 The Soul of the Nation

If we accept Joseph de Maistre’s claim that every nation has the government it deserves (which the Czech President repeated in his New Year message this year), and I believe there are good grounds for accepting this, we should ask what is wrong with the soul of the nation, that it should deserve the institutions it does not trust and has no respect for? In today’s terms: what is the political culture of post-Communism, which finds its expression in nation-wide behaviour and, in turn, in the way the country is governed?

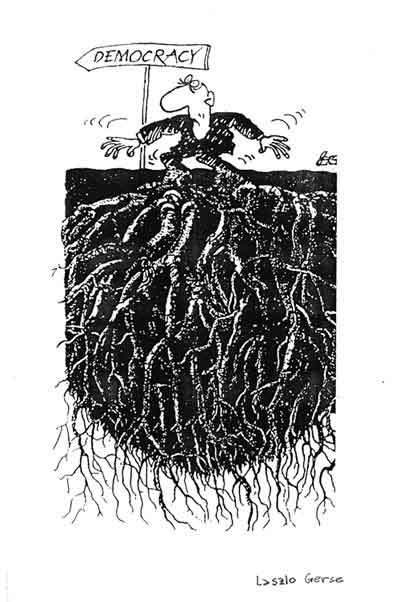

Let me introduce this section with a cartoon of the early 1990s in which a Hungarian cartoonist expressed an important insight into the post-Communist cultural dilemma. The cartoon tellingly conveys the depths of old hidden (possibly still partly Communist?) values and ways of thinking, which prevent liberal democracy from prospering. The Central European ‘backsliding’ of Gati and Conley refers to this. The task is to drag oneself up by one’s own bootstraps. At the same time, the cartoon is misleading: it suffers from the ‘liberal illusion’, that, once one cuts oneself off from one’s prejudices (in Gadamer’s sense, alternatively, the term illusions can be used), one spontaneously embraces the free market and democracy.

Table 3: The Soul of the Nation

Demographic behaviour, which reveals the most inner motives of men and women, seems to relate somewhat to Catholic/Anglican religiosity, but the latter can only be seen as one of many factors. However, if we look at the corruption indices below, which are directly relevant to good governance, we find no relation to Catholic religiosity.

Table 4: Bribes and Corruption

The ‘Corruption impact’ data for the UK seems rather high and I suspect that their inter-country comparison may not be very meaningful. However the Corruption Perception Indices (CPI) are comparable to a great extent (they have been constructed for that: their input includes external expert assessments) and the ‘Paid-a-Bribe’ percentage should be comparable, too, providing the questionnaires elicit truthful replies.

Compare Poland and the Czech Republic and note the discrepancy between the CPI and the Corruption impact indices on one side and the percentage of respondents who admitted that they had paid a bribe on the other side. I will return to this comparison after describing the main political cleavages in the Czech Republic. They are an important factor in the political mind of the nation.

4 Interpretation: the art of governance

The CPI indices can be used as a proxy for the ‘strength’ of the state, that is, for the effectiveness of the administration of the state (as contrasted with the ‘width’ or ‘breadth’ of the state, measured in terms of the number of varied tasks it tries to perform. Fukuyama 2004). A strong state in this sense testifies to a mature ‘art of governance’ that has been consistently performed by political elites for generations.

I use the term ‘the art of governance’ as shorthand for a set of values, character qualities, virtues, as well as actual skills, which make for good statesmanship. Perhaps the term ‘statecraft’ could be used as well. Old ‘mirrors of princes’ tried to describe and teach it. It includes: first, a careful attention to appropriate skills needed for a proper performance of the ‘sovereign’s three duties’; second and related to the first, constant attention to moral legitimacy, so that the people have an ongoing awareness and conviction that the supreme national authority and the regime in its basics is good and ‘right’ (a recent film, The Queen, was about a crisis in this conviction and its restoration).

The art of governance is an important element of political culture. It is developed over generations by the political elites of a country.

Using the concept of the strength of the state as above, one would expect that the political stability of the state would have something to do with its strength. A diagram, which links the historical stability of democratic states with their strength (approximated by the CPI 2000) explores this relation. It is assumed that the art of governance and the resulting strength of the state are part of a tradition going back for decades and even centuries.

Diagram 2: Democratic Stability

(Note that the order of post-communist countries by CPI 2000 was somewhat different from that in 2005: I return to the development of the countries below.)

The spread of the countries falls into three distinct groups in the diagram labeled as ‘mature civil societies’, ‘elitist civil societies’, and ‘post-Communist societies’. A statistical and historical analysis on the whole confirms Max Weber’s theory of the origin of capitalism and Barrington Moore’s theory of the origin of democracy. It is the maturity of a civil society (that has independent, responsible, and morally strong merchants, bankers, and entrepreneurs, creating political elites and building ‘their’ state) which is decisive. (Rychetnik 2003)

The Czechs have been regularly losing their political elites as a consequence of waves of foreign occupation, the emigration of the elite and its decimation, starting with the emigration of the Protestant nobles in 1620 and the subsequent Thirty Years War. The Poles and Hungarians have managed better to preserve their elites but their state does not seem to be stronger or more efficient than the Czech one. The indices and the data on people’s trust suggests that the Hungarian state, in particular, is better governed and administered, but the recent violence in the streets of Budapest indicates a deeply divided political class. Remembering again the wisdom of Joseph de Maistre, apparently we need not only to investigate the art of governance of the political elites, but also to look at its spread among the public in general.

A relatively high percentage of the Czech general public has admitted to paying bribes. On the other hand the Czech CPI (which examines political and administrative elites), while being low, is presently still better than the Polish one. This would seem to be consistent with a statement made by the former Director of Public Prosecution, Marie Benešová, in a BBC interview (2004), which two years later, when she was already out of office, she repeated and actually reinforced in a newspaper interview. She spoke about corruption in many town councils and characterised them as ‘little Palermos’. These are minor local elites, for which cronyism, mainly in procuring public construction projects, is a customary way of doing business.

Czechs in general dislike following rules. They prefer to cut corners, or manipulate the rules. This is another very old historical ‘root’. Czechs survived centuries of foreign rule by doing this. The traffic code is a case in point: since the penalties for breaking the code were stiffened two years ago (which significantly reduced the number of road deaths), some MPs have been trying to soften the rules again. But such cultural features are incompatible with the rule of law. The rule of law needs its citizens to cherish and obey the laws.

A stable democratic state needs citizens who are proud of their government and loyal to it and show their loyalty through their behaviour. This includes a demanding relationship with the political elites: they must be persistently watched and reminded of their duty to be good servants of the public and the state. On the side of the elites, it includes being responsive to these demands and a proper attention to the multiple tasks of governance and justice. (When I write about this point in Czech I like to quote a maxim which I learned in this country: ‘Justice must be done and must be seen to be done’.)

This is the point which the ‘Roots’ cartoon does not convey. It is not enough to cut off the old roots. People must acquire new roots that are proper for free, active and law-obeying citizens. It is a question of cultivating a democratic, participating and responsible political culture. It is a matter of growing a mature civil society. This is a perennial problem of new democracies. From the start the founders of Czechoslovakia were aware of it. Thomas Masaryk observed in his aphoristic manner in the early 1920s: ‘Once we have a democracy, we need democrats’. Fifty years of dictatorial or totalitarian rule only made it worse.

What is needed is a model; an attractive, realistic and practical ideal of what makes a good citizen and a good administrator and governor. This brings us back to the task of pulling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps. It is about changing those elements of your consciousness which you take for granted and changing them into that about which you have only a vague idea. People understand the concept of political culture as being the public behaviour of people in the public eye and assess it as ‘bad’ in opinion polls. But the polls do not investigate the depth of understanding and whether it includes self-assessment.

Corruption is understood as the misuse of public office or position of power for private, personal or party, gain. At the level observed in Central Europe it is no more an exception or a deviation, but the norm. It is systemic corruption; it is part of the tools of governance, part of the system of social coordination (Tomášek 2006). This is the theoretical explanation for its persistence and the lack of political will to tackle it seriously.

My conclusion from the above outline of the political culture is that it is not congenial to a stable (constitutional) democratic regime. Using the sociologists’ terms of social integration and system integration (Wrong 1994), my claim is that the inadequacies in the work of the police and the judiciary which result in an inadequate rule of law, and the observed or suspected degree of corruption in town councils and higher politics, tend to delegitimise the system as a whole. (I refer here to a performance-based legitimacy, a necessary complement to the source of power-based legitimacy, which a regime, originating in free elections, can claim.) The politics, and administration and justice subsystems tend to disintegrate the higher system. On the other hand, local government enjoys the trust of some two-thirds of respondents, much more than any central institution, apart from the President. Perhaps local councils are seen as less corrupt than some town councils or, perhaps, a moderate degree of local cronyism actually supports social integration at the local level (‘dirty togetherness’).

The legitimacy of a failing regime has to be supported by less savoury means, be it the toleration of corruption, confrontational politics, ethnic nationalism, fundamentalist ideology (the Czech Republic in particular suffers from the first two). Post-Communism reminds us of an unstable pre-war Central Europe. This would be my interpretation of the ‘political turmoil’ and ‘backsliding in Central Europe’ of Gati and Conley, which I quoted at the beginning.

Fortunately the influence of being a member of the EU, both (and perhaps even more) when we were aspiring to join, and now as actual members, makes a positive difference. It generates pressure on potentially corrupt elites (hence it is also a source of euro-scepticism) and it offers moral, organisational and financial support to anti-corruption elements in civil society. I can therefore end this section on a more positive note and add that, in spite of everything, some progress has been made and, I hope, can still be made. The Czech Republic was listed among twelve countries in 2006 which have made significant progress since 2005. Since the indices started to be published the rating went down and then up.

Table 4 continued: CPI 1998 – 2006

5 Can Politics Change the Culture and Save it from Itself?

The late American Senator Daniel Moynihan is the author of the following words:

The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society. The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself. (Harrison 2006)

However for the Czech Republic and other post-Communist countries it is a vital question: How is it possible to cultivate the culture of the rule of law and a liberal democratic culture in general? I would very much appreciate your comments and ideas on this point.

The initiatives mentioned below are based on the hopeful assumption that at least some elements of political culture can be improved.

6 Initiatives

Out of many initiatives, I will mention only a few: those which focus on the problem of political culture and order, and in which I have been involved.

The Christian and Labour Movement in the Czech Republic – KAP [www.hkap.cz]

KAP was founded in October 1996. Its aim is to study and spread the social teaching of the Church and apply it to social life . It organises social events for members through local organisations in Prague, Brno and Frýdek-Místek (Northern Moravia), and seminars (once or twice a year), the latter often in collaboration with the German and/or Austrian KAB. Financial support is gratefully received from the EC and EZA (Europäisches Zentrum für Arbeitsnehmerfragen). One of the more successful international seminars was held in Bor/Heid near Tachov (North-Western Bohemia) in 2003 to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the Bor Theses. They were one of the first attempts to form a theoretical Catholic position on the social situation of workers in modern times. The 2004 (September) seminar was about ‘Financial crises and their consequences for the world of labour’. The title of the 2005 (November) seminar was ‘Growing Differences between Poverty and Riches – a danger for employees and social dialogue in Europe’. The last 2006 (September) seminar was about ‘Ethics in Business. How to Achieve a Just World of Labour’.

Although the Movement started (by a North Moravian barrister) as a Christian Trade Union it soon changed into an educational association. Its seminars are well attended and visitors and contributors come from Slovakia, Germany, Austria, and Italy. KAP members have been active in the following initiative.

In 1998 the Czech Bishops Conference decided to prepare a document on social issues (following a similar initiative of bishops in England and Wales, Germany, Austria, Hungary and the USA). A team of experts was headed by an economist, Professor Lubomír Mlčoch. A few months later experts nominated by the Ecumenical Council joined in. The document, called Peace and Good, was issued in November 2000 and published in 2001 (English and German versions are available). The whole of Chapter 5 is devoted to the relations between ‘the state and civil society, the renewal of legal order and a growth towards responsible citizenship’. The document had a mixed reception, even within the Church. Part of the political spectrum labeled it as negativistic and hostile to post-Communist achievements. The discussion was summarised in sequel, Harvest of Public Discussion on Peace and Good (in Czech and German), which was published in 2002. One of the issues discussed was whether Christians can act as ‘an island of positive deviation’. Many of them still feel that social and political concerns, apart from traditional charity, are not appropriate for a Christian.

[http://tisk.cirkev.cz/dokumenty/pokoj-a-dobro.html]

[http://tisk.cirkev.cz/dokumenty/en-verejne-diskuse-k-listu-pokoj-a-dobro.html]

Another civil association with some 500 members has a history starting soon after the Communist takeover in 1948. It is called ‘The Democratic Club’. Its task is to unite people of various political hues in an effort to support democratic institutions and develop democratic culture. It considers itself a guardian of democracy. It organises discussions, publishes a bimonthly newsletter, and occasionally issues a statement on a topical theme. One is being prepared at present on the voting system, regarding how better to express the stipulated constitutional principle of proportional representation. Unfortunately, not all members are convinced that the rule of law and good governance are prerequisites of democracy and many are hesitant to involve the club in controversies on this point.

[http://www.volny.cz/dklub/] (English, German, French, and Esperanto summaries)

In 2003 an ‘Institute for Economic and Political Culture’ was established as a civil association of some 15 members. The Institute works on projects financed by grants (no project is running at present). Its first project was about lobbying and how it should be regulated. The experience of various countries was analysed and the analyses were published in a brochure. A seminar in December 2004 discussed the material and again its proceedings were published in 2005. The institute continued its work with another project in 2006/7, with the translation and publication of Robert’s Rules of Order.

[www.ipek.cz] (one or two documents are available in English)

Discussion

Discussion

Prof. Dennis O’Keeffe: Over the quarter of a century during which I have been visiting communist and post-communist Central- and Eastern-Europe, it has gradually become my belief that a comparative ‘theory of emulation’ might be useful to understanding what has happened in these countries. It seems to me that almost everywhere in the post-communist world economic imitation is proving much more successful than political imitation. These countries want to become rich, free and constitutional, but they are in fact getting rich much more successfully than they are learning to be either free or constitutional.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: It is certainly true that changes in political culture take longer to achieve. I am confident that young people who now go abroad to study, whether in Western Europe, the United States, Australia, Britain or wherever, and then return to their native countries can constitute the basis for a new citizenship. In the short run, however, a lecturer may speak about the rule of law in theory without having any impact upon the underlying political culture of a country.

Dr. Maria Nuila: Do you think that corruption, in certain sectors, is linked with poverty? If so, can it be said that, the poorer the place, the more likely it is to become corrupted? What type of corruption are we talking about – is it state corruption?

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: The indexes measure corruption in politics and administration. There are, of course, other kinds of corruption – for example, in education – which are not included in the general indexes, but which are considered when interviewed persons are asked whether or not they have paid a bribe in the recent past.

As to the relation between poverty and corruption, it is observable that by the indexes the most corrupt countries are generally found in Africa, but still I see no direct correlation between the two. I tend to associate a lower level of state corruption with the presence of a responsible civil society – a situation in which the state is considered as a tool, as happens in Britain. In this condition, people want the state to be a good tool, so they keep an eye on it. It is noticeable that constitutional monarchies – in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, and Britain – tend to have better civil services, perhaps because of some longstanding tradition of royal government in which the king sees himself as the guardian of justice. When these monarchies became ‘constitutional’, the tradition of a loyal civil service was already in place. In the United States and Switzerland autonomous civil societies created their own states (and civil services) for their own protection and kept them efficient.

Russell Wilcox: Are there theoretical approaches that explain why different regions of Europe differ in relation to their political economy?

I also wonder who coined the working definition of ‘corruption’ you are using. What are the purposes behind such definition ? From where do you draw the standards against which corruption is assessed?

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: In relation to your first question, we have already seen that there are significant differences in levels of corruption between European countries, and that on the graph these countries tend to aggregate in clusters corresponding to specific regions – Continental Europe, Atlantic Europe, Central-Eastern Europe. My interpretation of this is that in Continental Europe we have seen the development of étatist civil societies, with a limited autonomous entrepreneurship among the capitalist class, under centralised and non-constitutional monarchies. This is clearly different from the political and social milieu of Atlantic Europe. Max Weber and Barrington Moore wrote about it.

As to your second point, Transparency International defines corruption as ‘a misuse of a public position or office for private, personal or party-political profit’. In this sense any use of a position of power to favour one’s own party is already corruption.

Russell Wilcox: But in some contexts, such as in semi-tribal societies, the differentiation between private and public is not at all clear, and the notion of ‘corruption’ Western Europeans use hardly applicable. Some people would go as far as to claim that such a notion of ‘corruption’ is actually a form of neo-imperialist imposition. Moreover, they might also assert that the moral authority of Western States to effect such an imposition is severely compromised by their own deeper form of systemic corruption born of the intertwining of capital and politics.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: Certainly the analyses I have mentioned rest on the idea that it is possible to study culture objectively. The extent to which this assumption corresponds to truth and reality, I leave for enquiry by those engaged in theological or comparative cultural studies. As for myself, I try to look at culture as a tool humans use to work in their own environment. In this sense, I suppose, I could be styled an ‘imperialist’, as I believe that Western culture is more advanced in supporting the development of people. Still, there are doubts. Is our development sustainable in relation to our environment? To what extent is the Western system politically stable?

Jana Tutkova: I believe virtue builds upon virtue. In the U.K. or Holland, and in other countries which seem not corrupt in the sense that people may not use public offices for their own benefit, various forms of ‘commodification’ of the human being are nonetheless widely accepted. Reports have been published recently claiming, for instance, that London has the highest crime rate in Europe and the highest drug addiction rate in the U.K. We already know about high rates in teenage pregnancy, family break-up and abortion. These, I would suggest, are cases of a somehow ‘hidden’ corruption. Sometimes, furthermore, even in Britain open corruption in your stricter sense comes to the surface. We have all heard recent stories of peerages and positions following donations to party-political funds. Some peers connected with biotech industries have pushed for cloning and the adoption of other biotechnologies. From my knowledge of the dynamics of the European Parliament I am also conscious that ‘lobbying’ might be considered a legalised or ‘smart’ form of corruption.

What I want to stress with all this is that your definition of corruption focuses too much on the misuse of public funds or goods by those holding public office. By taking this line, your approach is very much linked to a twentieth-century, left-right scale. If you were instead to approach this from the position in which we are at this very day, I believe you should adopt a different scale, one contrasting a ‘culture of life’ with a ‘culture of death’. From this perspective, the notion of corruption should be linked less to attitudes towards goods and more to attitudes towards other persons. It would be interesting to see where the Czech Republic would stand in such a scale.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: I have no doubt that Western civilisation is in crisis. This we can see clearly from its declining birth rate, and from the consequent need of importing workers from other cultural backgrounds. Looking at Western films and television, it is possible to see just how pervasive this ‘culture of death’ is. These are certainly questions that need to be addressed at a global level. What I am trying to achieve in the Czech Republic is simply to reach a level of rule-of-law comparable to Western countries. I expect politicians to do what they are expected to do in civilised societies – keeping order and justice, and refraining from corruption; and I would like the citizens to do their part – honouring the laws and keeping an eye on the politicians and administrators. I am not, therefore, directly tackling the issues you have raised, although I recognise them as real problems.

As to where Czech Republic might stand in relation to your scale, I refer you again to the cleavage in society between ‘idealists’ and ‘pragmatists’ mentioned earlier. Some politicians would say that there is no objective morality, while others argue about good and evil. A continuing, often coded, discussion is taking place. No position has prevailed nor is it likely to do so.

Joseph Egerton: I am, I have to say, profoundly cynical about any attempt to control corruption by almost any means. In this country, when we look at private papers relating to what are supposed to be the less corrupt governments – such as Stanley Baldwin’s –, all sorts of illegal practices come to the surface. It seems to me that, as far as the ability of a society to survive is concerned, the first test is G.K. Chesterton’s ‘a nation is something for which people are willing to die’. In 1940 the British were willing to die rather than surrender; the French Third Republic failed to obtain this level of support from the French people. One of the questions you might usefully ask is: what level of social commitment is there in Poland, in the Czech Republic and in other Central- and Eastern-European countries for them to survive and succeed? This is not quite the same thing as measuring levels of corruption in these countries, since some deeply corrupt countries survive remarkably well at times.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: You remind me of the definition of corruption used by Machiavelli, one which measured what individuals were prepared to do for their country. By this standard, the Romans were a less corrupt civilisation, as they were willing to die – or to put their hand into the fire – for their country. What I have been using here are measures proposed by Transparency International and used by the programme of which I have spoken, but they certainly do not capture all aspects of virtue or corruption.

[After the discussion the Speaker felt he should add to this response in correspondence with Joseph Egerton and, with his permission, a more extended response is introduced immediately below in Italics.]

I recognise that the virtues of honesty and integrity (absence of corruption in the Transparency International definition) on the one side and Machiavelli’s ‘communal’ virtue of willingness to die for one’s nation on the other are two different things. In my talk I relied on an implicit assumption, namely that a regime considered as legitimate not only from its source in democratic elections but also through its satisfactory performance of the three duties of the sovereign has a better chance of eliciting loyal support in the face of internal or external threats. People will be ready to defend a regime which most of them consider as offering good conditions for their own efforts and business of living, simply because it is in their own interest. A democratic regime, wherein political and administrative elites are not (TI) corrupt, is respected, elicits national pride and is considered worth certain sacrifices.This self-interest motive, however, is clearly not enough. There must be other motives, too, such as the moral legitimacy of the regime (which I mentioned in the talk), emotional commitment to one’s home, etc. What I was addressing was mainly a ‘performance legitimacy’ which, if missing, destabilises a regime. This was my interpretation of post-communist Central-European instability and ‘turmoil’.

Michael Elmer: Given the picture you have given of attitudes towards democracy in Central Europe, what explains the noticeably high degree of pro-democratic evangelism found in the Czech Republic in regard of repressive regimes elsewhere in the world? I am thinking of the particularly forward position of the Czech Republic vis-à-vis Cuba. Much more is done in the Czech Republic to shine light on what is happening in Cuba than is the case, for example, in Poland, Hungary, Slovakia or other comparable Central- and Eastern-European states.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: I can see two reasons for that. First, the Czech Republic is now returning to its pre-World War II traditions. The Czech Republic was the first democratic state in Central Europe, and it is therefore particularly sensitive to issues of democracy and democratisation. Secondly, you must take into account the personal influence of President Havel and the impact of the overall change in the regime after the revolution. Previously, the Communist regime in the Czech Republic was more oppressive than in any other Central-European country. Other Communist states experienced a gradual breaking-up of their regimes during the 1970s and 1980s. Even after the big change, the Communists of the Czech Republic did not change their name. They simply renounced the ‘excesses’ of earlier years. For this reason, the Communist Party, while quite strong in Parliament, is still considered a pariah and outside the mainstream political spectrum. These two factors – a democratic tradition and recent anti-Communist history – do, to my understanding, explain the stand taken by the country in the international arena today. Czech dissidents are, furthermore, very conscious just how useful foreign support was to them in the years of the Communist regime.

Neil Pickering: With your experience of the Czech Republic, how do you see the future of a country like China, now running what might be described as a form of ‘state-controlled capitalism’? How long can a very tight system of central planning and control be combined with market mechanisms? How might economic reforms spill over into political reforms?

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: I do not dare to make any assessment of China. It is a fascinating civilisation. I see an ancient political and social wisdom still operating underneath the change from pure Communism to the present system. Such gradual change might not have worked in Europe, but it has worked in China as basic market-behaviour routines were not completely destroyed there, as was the case in Russia, under Communism. Still, I cannot completely explain the present, and certainly cannot predict the future of that country.

Dr. Andrew Hegarty: China is, in a way, managing its own transition, but it is managing in some respects at a very slow tempo. This brings me to something that has been in my mind during the whole of this seminar, namely the issue of the speed of change. I have not read Vaclav Havel’s recent book, but I did read in the last issue of the New York Review of Books a substantial portion of an interview he gave some time ago to a journalist. This focused quite heavily on his relations with Vaclav Klaus. Havel clearly thought Klaus rather brutal and hasty in the manner of his implementing of privatisation. Is there, do you think, a sense in which an overhasty transition from one system to another, without a culture change, almost necessarily brings on a period of corruption, as people try to live in an unfamiliar new world wherein some of the ‘weak’ cannot cope?

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: I think that is to some extent so. Consider the murder-rate in the Czech Republic. This has risen significantly after 1989. This can only be attributed to a disruption of order that took place with the revolution. Francis Fukuyama and others have written of the consequences of such a disruption of order. Klaus, however, thought this unimportant; since he was convinced that the hidden hand of the market would solve everything. Few understood the problems associated with the continued presence of old Communists in the judiciary, its overall weakness, and the need for a true culture-change there. Such matters were simply not considered important for the development of the country. I would not, however, blame Klaus only. The Washington Consensus advice was also misleading and insufficient.

Russell Wilcox: This is one of the reasons why the Chinese government was so firm in its crackdown over the Tienanmen Square revolt. It was terrified that what had happened in Central- and Eastern-Europe, and in Russia, might also occur in China, and it was determined to ensure that it did not. It also saw that a too rapid transition to a market economy would have been even more devastating for China than for Russia and the former Communist countries of Europe.

Do you think there is greater corruption in post-Communist Russia than in post-Communist Central- and Eastern-Europe and, if so, why?

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: The indexes show that Russia has much higher corruption rates. The reason is that Central-Europe has some traditional rule-of-law notions that set certain minimum standards that people will generally not transgress. In the Czech Republic civil society was also in some respects quite developed before World War II. The shock-therapy of privatisation was quite similar in Russia and in the Czech Republic, and if corruption in the latter did not go so far it was because of these hidden assumptions.

Prof. Dennis O’Keeffe: I realise we have run out of time, and would like simply to observe that there is another problem upon which we have not touched: the willingness of persons implicated in the previous regimes to consider their past. Such elites are the remnants of some of the most criminal ruling groups the world has ever seen. If democratic and constitutional reforms were implemented too rapidly, they would be exposed while still alive, and that is manifestly not in their interest. I refer above all to the situation of China. The world is astounded at its recent economic growth. The Chinese elite are silent about the vast criminality of Communist China’s history.

Dr. Ludek Rychetnik: Yes, there is certainly something in that.

References

- Marie Benešová, BBC interview with Václav Moravec, 8 April 2004

- CVVM, Centre of Public Opinion Research (in Czech, English summaries) [www.cvvm.cas.cz]

- Bohumil Doležal Political Notebook (in Czech, German, Hungarian, Polish) [www.bohumildolezal.cz]

- Francis Fukuyama, State Building: Governance and World Order in the Twenty-first Century. London, 2004

- Charles Gati, Heather Conley ‘Backsliding in Central Europe’, International Herald Tribune, April 3 2007

- Lawrence E. Harrison, The Central Liberal Truth. Oxford, 2006

- J. Hellman, G. Jones, D. Kaufmann ‘Seize the State, Seize the Day: State Capture, Corruption and Influence in Transition’, World Bank, 2000 [www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance/pubs/seizestate.html]

- IPEK, Lobbyism versus Corruption I, II, 2004(I) 2005(II) (in Czech) [www.ipek.cz]

- Barrington Moore Jr, Social origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Harmondsworth, 1966

- Ludek Rychetnik, ‘Protestant ethics and constitutional stability: the search for order based on freedom’, Finance and Common Good. Université de Fribourg, Geneva, 2003: 130-141, 168-9

- Jeffrey D. Sachs and Katharina Pistor 1997 The Rule of Law and Economic Reform in Russia. Boulder CO, 1997

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents, Harmondsworth, 2003

- Marcel Tomášek, ‘Systemic sources of corruption during social change from a macro-sociological point of view’ (in Czech), in B. Dančák, V. Hloušek, V. Šimíček (eds) Korupce. Projevy a Potírání v ČR a EU: Brno, 2006, IIPS: 31-44

- Transparency International, National Integrity System Sourcebook, 2000 [www.transparency.org]

- Transparency International, Global Corruption Barometer. Corruption Perception Indices, 2006 [www.transparency.org]

- Max Weber, The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism [1904-5]. London, 1992

- Denns H. Wrong, The Problem of Order: What Unites and Divides Society. New York, 1994

- Peace and Good, 2001, Secretariat of the Czech Bishops’ Conference

- Harvest of Public Discussion on Peace and Good, 2002 (in Czech and German), Secretariat of the Czech Bishops’ Conference