Published on

21 August 2006

Integrity and Conscience in the Life and Thought of Thomas More

By: Prof. Gerald Wegemer— 2005-2006

ABOUT

Prof. Gerald Wegemer is Professor of Literature, University of Dallas, U.S.A. Seminar on Monday 21 August 2006

At the age of fifty-six – thirteen months after his resignation as Lord Chancellor of England, ten months before his arrest, and two years before his death – Thomas More wrote the epitaph for his tomb, had it engraved in stone, and sent a written copy to Erasmus for publication. More explained this odd action in his letter to Erasmus: ‘I considered it my duty to protect the integrity of my reputation’. He explained this epitaph as ‘a public declaration of the actual facts’ which publicly invited rebuttal – as a seasoned and shrewd lawyer would do. The letter also set forth a brief summary of what had occurred since his resignation: in thirteen months, he wrote, ‘no one has advanced a complaint against my integrity’. Quite the contrary, ‘it is embarrassing for me to relate’, More went on, that the king has pronounced ‘frequently in private, and twice in public that he had unwillingly yielded to my request for resignation’. More also reported that Henry VIII, in demonstration of his good will, had both the Duke of Norfolk and the next Lord Chancellor express the King’s gratitude to More ‘at a solemn session of the Lords and Commons’ and on ‘the formal occasion of [the Lord Chancellor’s] opening address’ to Parliament. What More did by publishing his own epitaph was literally to chisel in stone proof of his reputation for life-long integrity. More acknowledged that some would accuse him of boasting, but he argued that his duty to protect his reputation for integrity overrode that concern.

This preoccupation with integrity – with consistency between thought and action – had marked More’s entire life.

This preoccupation with integrity – with consistency between thought and action – had marked More’s entire life.

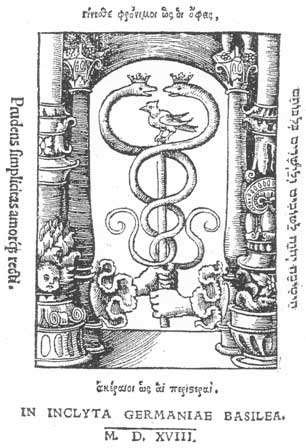

For example, at the beginning of his career, More at least twice reminded civic leaders of the snake and the dove that you have pictured on your handout. This device was published in More’s 1518 Utopia and it represents the multicultural agreement spanning many centuries that an upright life, made possible in part by shrewd serpent-like prudence, is essential for a happy life. (Notice that two very well-trained serpents – ordered to form the image of health – are needed to safeguard one dove!) At the end of his career, while in prison, More again forcefully reminded future leaders that Christ commanded his followers to be ‘as wise as serpents yet innocent as doves’, thus being ‘brave and prudent soldiers, not senseless and foolish’ ones.

To understand Thomas More, and the entire Renaissance project of which he was the first major English figure, one must understand the central role that education of the whole person played in the quest of Renaissance humanists for international peace and prosperity. The education they proposed aimed at both mind and character, the same type of education that had also been the pre-eminent concern of the classical Greek and Roman authors that More, Erasmus, and others wished to see reborn.

Why this classical and Renaissance concern for ‘character’, in Greek, ethos? Quite simply because, as Aristotle put it, ‘as we are , so do we judge’. Experience shows that persons enslaved by uncontrolled anger or burning ambition or blinding greed cannot judge clearly; they lack the integrity of self-government that human beings need for consistent sharp-sightedness and, consequently, for prudent action.

One of the most famous classical examples to illustrate the connection between character, accurate perception, and good government is the captain of a ship at sea, an image that More used throughout his life. As he put it in his first major work: ‘You must not abandon the ship in a storm because you cannot control the wind’. In fact, the captain must have taken great care beforehand to understand the ship, the sea, and the winds if he were to fulfil his task of guiding the ship to port. In his last work, written in the Tower, after a full life of experience both theoretical and practical, Sir Thomas used the same image and warned that the weight and difficulties of duties can ‘so grip the mind that its strength is sapped and reason gives up the reins’ (Complete Works v. 14, p. 263). At such times, the weight of these duties could lead anyone to ‘neglect to do what the duty of his office requires (…) like a cowardly ship’s captain who is so disheartened by the furious din of a storm that he deserts the helm, hides away cowering in some cranny, and abandons the ship to the waves’ (CW 14, 265). More goes on to indicate in no uncertain terms that such a captain could never be called good or just. As More used this image, he showed that the captain’s character, his ethos, is at least as important as his intellect or his skill. He showed that a certain kind of character is needed to free the intellect to utilise the necessary skill.

That More thought deeply about these matters over decades is seen clearly not only in his decision to master Greek as soon as he had completed his legal training, but also, during the same period, by his series of public lectures in London on St. Augustine’s thousand-page assessment of political life, The City of God. More was so concerned about the challenges of temporal justice that, with Erasmus, he mastered Greek in three years and spent an entire decade studying the Greek and Latin thinkers to understand what had been done in other ages and other cultures to achieve some measure of justice in a world that often seems more cruel than good, at war more often than at peace. At the same time, More gathered experience and skill in the day-to-day workings of the city. He practised law by serving as Undersheriff of London and working on public projects such as the construction of urgently needed sewers to control the ever-flooding River Thames. By the time More accepted a position at King Henry’s court – at age forty-one – he brought an immense competence and an unquestioned reputation based on his wealth of knowledge and experience. Apart from being recognised as one of the outstanding thinkers of his day, he had been a judge for eight years; a Member of Parliament twice; among the most active and prominent lawyers of London; spokesman, negotiator, and member of London’s most powerful guild; a poet and public orator; an ambassador on two foreign embassies; twice chosen as a reader to lecture in law at his inn of court; the father and educator of his children who insisted that his brilliant daughters receive the same education as his son, even though excluded from the Oxford More had attended.

Along with this wide-ranging practical experience and thorough mastery of English law, More entered the King’s service with a well-developed political philosophy. After twenty years with such teachers as Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Cicero, the Bible and the early Church Fathers both Greek and Latin, as well as the medieval and English traditions of Common Law and political practice, More’s political philosophy gave first place to clear-sighted reason, strong character, just law, and a culture that fosters reason, character, and law as the necessary foundations of good political life. Yet he realised that to expect reason, character, and law to exercise such power was almost utopian, given the fact that history seems to present more war than peace, more discord than harmony. Nonetheless, he saw this daunting task to be possible only if law and education-in-character strengthened and supported reason over passion, prejudice, and thoughtless self-interest. This task was, and is, so difficult, that most legal and political philosophers after More abandoned the cultural project which he and his Renaissance and classical predecessors saw as the irreplaceable support for just government. It should be no surprise, then, that More is the first person in English to use the word ‘culture’ as we use it today.

With his extensive experience and with one of the finest education which any individual has ever received, More is explicit about what he considered most important in his own children’s educations. As he wrote in a letter to their teacher:

The whole fruit of their [educational] endeavours should consist in the testimony of God and a good conscience. Thus they will be inwardly calm and at peace and neither stirred by praise of flatterers nor stung by the follies of unlearned mockers of learning (…). A mind must be uneasy which ever wavers between joy and sadness because of others’ opinions. (Thomas More Source Book, 199-200)

More insists: ‘put virtue in the first place (…), learning in the second’ (199), and he concludes this letter with the wish that his children come ‘to love good advice’ (200). This is the concluding wish of a person who knew that conscience can be clear-sighted and strong only if one’s character has been freely formed – cultivated – to love the truth as shown by such an ardent desire for good advice. Notice here the centrality that More gives to conscience and culture, and notice also the effect he knew it would have: it would bring the very calm and peace that More demonstrated at the end of his own life.

The concept of ‘integrity’ is immensely important in understanding Thomas More – as well as the classical and Renaissance projects – because integrity describes actions of character that conform to conscience. And conscience More knew to be the metaphysical foundation for justice and law, arising from the very structure of our being. More was the first to use the word ‘integrity’ as we use it today, and he shows that integrity is impossible without a conscience guided by just law and long reflection upon the character of just law.

More understood the day-to-day exercise of conscience as the hard and diligent work of seeing the actual circumstances of a particular action and then judging them in light of principles of right and justice, principles which have been discovered by the deeper long-term action of conscience – not principles willed or created. Hence the need for good counsel. This kind of judgement takes a great deal of training if it is to be done well and with accuracy, as More showed in his own life and as the best lawyers and law schools show in their training. Not only did More study for a decade in earnest after law school and before entering national politics, but he said that he spent another seven years carefully studying the specific issues that would lead to his resignation, imprisonment, and death.

Conscience, however, no matter how much it has been ordered to the true and just, can still be erroneous – and that is precisely why More wanted his children to love good advice and why he gave a principled argument for free speech when he was Speaker of the House of Commons, the first such argument recorded in history. The reason he gave for free speech is simple, but profound: we need other minds to be in conversation with ours because every person is limited and flawed and free, free enough to reject what is true; and for that reason More did not think that any one person should be given absolute rule, because every person makes mistakes and is subject to the ‘foolish fantasies’ of pride. For this reason, all people – even kings – need good laws that have arisen from the best work of those wise minds who went before them. For this reason, everyone needs a circle of good-willed and clear-thinking friends who have formed their characters to shun flattery and to love truth.

To understand this point, we could look by way of contrast, at one of the most dramatic examples from the last century of what happens when we do not attend to conscience with the help of clear-thinking friends. What follows is a quote from Albert Speer, one of Hitler’s inner circle, taken from his best-selling book, Inside the Third Reich. Writing after the Nuremberg Trial and after twenty years in prison, he explained:

During the twenty years I spent in Spandau prison, I often asked myself what I would have done if I had recognised Hitler’s real face and the true nature of the regime he had established. The answer was banal and dispiriting: my position as Hitler’s architect had soon become indispensable to me. Not yet thirty, I saw before me the most exciting prospects an architect can dream of.

Moreover, the intensity with which I went at my work repressed problems that I ought to have faced. A good many perplexities were smothered by my daily rush. In writing these memoirs I became increasingly astonished to realize that before 1944 I so rarely – in fact almost never – found the time to reflect upon myself or my own activities, that I never gave my own existence a thought (…). (p.64)

What was a challenge to Albert Speer in the 1940s is a challenge every busy and ambitious human being faces in applying the long and hard work of reason in resolving the great problems and perplexities that personal, professional and political life poses.

In this context, one can appreciate why Thomas More disagreed fundamentally with Martin Luther in his claim that human nature and reason were so corrupt that they were powerless to find truth and justice, in his denial of free will, and in his belief in an elect. These beliefs were, in More’s judgement and in the judgement of every Christian king then in Europe, seditious opinions sure to lead to war and social chaos. The greatest evidence for this view – from their perspectives – was the Peasants’ Revolt of 1525 which ended with the slaughter of 70,000 peasants in one summer. Luther’s theory of a ‘pure elect’ saved by faith alone went against the entire humanist project advanced by More, Erasmus, and the other Renaissance advocates of international unity, peace and reform through the development of law, virtue, public deliberation, and education.

When in conversation with one of Luther’s followers who claimed that the personally inspired reading of the bible was sufficient education, More made this reply:

Now, in the studying of Scripture – in determining the meaning, in considering what you read, in pondering the theses of various commentaries, in putting together and comparing different texts that seem contradictory but are not – although I do not deny that grace and God’s special help are the great thing here, still he uses as an instrument for that purpose our reason. God helps us to eat also, but yet not without our mouth. And just as the hand becomes the more nimble by the performing of some feats, and the legs and feet the more swift and sure by the habit of going running, and the whole body the more wieldy and healthy by some kind of exercise, so too there is no doubt that by study, effort, and exercise in logic, philosophy, and the other liberal arts, reason is strengthened and quickened, and judgement, both in those liberal arts and also in orators, laws, and the writings of historians, is much ripened. And although poetry is by many people taken for nothing but painted words, it yet much helps the judgement and, among other things, makes one well equipped with one thing in particular without which all learning is half lame (…) a good mother wit. (TMSB 278)

For More, that ‘one thing (…) without which all learning is half lame’ is prudence. Socrates, Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca, Erasmus and all of More’s fellow Renaissance humanists agreed. As More put it clearly at the end of his life: ‘true strength of character – that strength which in rational creatures is called virtue – can never exist without prudence’.

More saw law itself as a work of prudence, yet, despite his respect for it, More had modest expectations since even the best laws cannot protect every innocent person. This view More learned from history and from his own experience: that often laws are, in words More quoted from Plutarch, ‘just like spiders’ webs; they would hold the weak and the delicate who might be caught in their meshes, but would be torn in pieces by the rich and powerful’. More was acutely aware from his earliest days that even the best laws could be manipulated unless learned, prudent, and courageous statesmen exercised constant vigilance.

The usual form of courage taken by statesmen is the skilful and prudent communication of the difficult counsel needed in attending to what the spirit of the laws requires.

To appreciate the skill and courage of Thomas More as a good counsellor, consider this example: his reply after the first time King Henry ‘requested’ his counsel about his divorce. At that time, his income depended on Henry, and More was also heavily in debt to the King after building the great house at Chelsea that he needed to conduct state business according to his new station.

As Roper reports, King Henry showed More the passages of Scripture that seemed to support the possibility of annulling his marriage to Queen Katherine. More immediately excused himself, saying that he was ‘one who never professed the study of divinity’. The King did not accept this disqualification and then ‘sore (…) pressed’ More to study the matter with several bishops who favoured the King’s interpretation (TMSB 32). After meeting with them and studying the matter on his own, More came back to Henry and said that he and the appointed bishops would not be ‘meet Counsellors for your Grace’ in this matter because, ‘being all your Grace’s own servants’, they were all receiving ‘manifold benefits daily’ from him. After pointing out this conflict of interest in so straightforward a manner, More then went on to recommend counsellors who would not ‘be inclined to deceive you’ out of ‘respect of their own worldly [advantage] [or] for fear of your princely authority’. And whom did More recommend? The ‘old holy doctors [of the Church], both Greek and Latin’.

This was a bold and unflattering but, as the following months and years showed, a highly skilful act of good counsel. As Roper went on to report – in what can be read as amazement and admiration – More ‘always most discreetly behaved himself’ and ‘so wisely tempered’ his counsels, that King Henry received ‘them in good part, and oftentimes had thereof conference with him again’. (33)

In fact, King Henry’s friendship and trust in Counsellor More was so great that, after five years of such discussions and continued disagreement, he still made him his Lord Chancellor.

More was always the truth-seeking Counsellor, and he indicated clearly at the end of his life – at his trial and again on the scaffold – that King Henry had been corrupted by those whose responsibility it was to advise truthfully and lawfully, but did not; King Henry had been corrupted by flatterers. As More had earlier warned the counsellor who was to replace him, Thomas Cromwell:

If you will follow my poor advice you shall, in counsel given to his Grace, ever tell him what he ought to do, but never tell him what he is able to do, so shall you show yourself a true faithful servant, and a right worthy Counsellor. For if the lion knew his own strength, hard were it for any man to rule him. (232)

More also showed his courage and shrewdness as the King’s Counsellor in his last and most famous quotation: ‘I die the king’s good servant, and God’s first’. More spoke these words on the scaffold, and when Henry heard them, he would have remembered the two most important conversations he ever had with Thomas; both conversations were about conscience.

One took place when More was forty-one. Before accepting King Henry’s invitation to serve at Court, More spoke to the King about conscience, and set forth one condition: that the King respect his conscience. Imagine the King’s surprise that a subject would be so bold as to make such an unflattering and uncompromising request. Yet, as More reported later, the King responded by giving the ‘most virtuous lesson that ever prince taught his servant’; the King responded by telling More that he should look first to God and conscience and then to the king. (TMSB 358) Notice the ‘and’, indicating the integrity which even King Henry assumed to be possible for human beings who have both natural and supernatural ends.

The second conversation took place before More accepted that highest office of Lord Chancellor. He had yet another bold conversation with Henry: again about conscience. And once again Henry gave More ‘the most virtuous lesson that ever prince taught his servant’: look first to God and conscience, and then to your king. Therefore, in his own last words, More made a powerful appeal to Henry’s own conscience by reminding the King of his own words and his own promises.

Since we are now considering the end of More’s life, let us consider the centrality of conscience and integrity by looking at several intriguing aspects of that end.

By the age of fifty-five, Thomas More had achieved as much fame, wealth, professional success, and genuine affection as any person could desire as a lawyer, judge, highest officer of the realm; husband, father, grandfather, popular citizen of London; international diplomat, trusted and brilliant negotiator, famed rhetorician and writer. And nevertheless, for what most called a foolish scruple of conscience, he threw all of that away and died three years later – alone – in broken health, and largely overlooked by the establishment for the next four hundred years. At his death, he was not understood by even one member of his family; his closest political colleagues abandoned him; none of the bishops except John Fisher stood by him; he was condemned as a traitor and his head was placed on London Bridge in disgrace.

Nonetheless, right up to the final moments of his life, More was not only calm but even merry. During his last year in prison, he repeated often the merry quip that ‘a man may lose his head and have no harm’. During the last hour and the very last minutes of his life, he joked with his jailer, then with his guard, and then with his executioner; by doing so, he provoked the criticism of the Tudor historian Edward Hall who was scandalised that More would end his life with ‘mocks’ and jests, lacking the dignity of his station.

After fifteen months in a damp, cold cell right next to the River Thames and directly over the Tower of London’s smelly and stagnant moat; in a cell so cold that ice formed on its walls since there was no glass in the arrow-slits that served as windows; after fifteen months in such conditions, in isolation, while suffering kidney stones and severe chest pains and debilitating leg cramps, More’s health was eventually so broken that he could not walk by himself up the stairs of the scaffold. So he quipped to his guard: If you help me up, I shall get myself down.* And when he got to the top and prudently paid his executioner a gold coin to encourage him to do his job well, More placed his head on the chopping block, after carefully moving his long beard out of the way, quipping to the executioner: Do not cut my beard; it was not found guilty of treason.* [*These are paraphrases, not direct quotations.]

To understand the serene and friendly good cheer that More exercised towards his betrayers even during the height of their injustice, is not an easy task, especially since he knew that he was witnessing the manipulation of parliament as well as an attack on his Church (which would soon be outlawed for some three hundred years). In the light of this, how could merry quips and silent capitulation be appropriate responses? Lord Acton, the famous British and Catholic historian of liberty, criticised More for dereliction of his duty as the captain of state, as the chief officer of England’s legal system, and as the leading voice in the fledgling English parliament. Why did More not speak out when Cranmer and Henry advanced the first defence of divine right in England?

Another set of questions is posed by Holbein, the most famous and skilful portrait painter of that age. More was his patron, and More brought him to England, where Holbein eventually made his fortune. Holbein stayed at the More home and came to know him quite well.

Not surprisingly, Holbein painted the best-known artistic representation of Sir Thomas, which you have on this small commemorative card. But why would Holbein show the serious and pensive Counsellor and statesman of fifty, not the merry Sir Thomas More, whom everyone loved? Why that serious pose, with no hint of the ever-joking Thomas More? Did Holbein consider this image, perhaps, more fitting to a lawyer-statesman confronted with grave issues of law and statecraft? And would Holbein have agreed with Hall that More’s ‘mocks’ at his death were unbecoming?

While you have that card, turn to the prayer on the inside, on the left. Look at the last line of the last prayer that More wrote on earth: ‘The things good Lord that I pray for, give me thy grace to labour for’. This prayer was written after More’s trial of July 1 and before his execution on July 6. What work could More possibly have had in mind during the last hours and days of his life? Was not his life’s work over by that time? What work could he possibly have had in mind during these last hours of his life?

The greatest enigma of More’s end, however, is the magnanimous friendship he showed to the very last days, hours, and minutes of that life.

This facet of More’s character strikes most men and women of long experience as his most remarkable and admirable feature: the loyalty of his friendship to the end, despite betrayal and blatant injustice. It is certainly the aspect of More’s life that captivated the five London playwrights, Shakespeare included, who wrote the Elizabethan play called Sir Thomas More that never made it past Elizabeth’s censors.

Faced with the fifteen judges who falsely condemned him, judges with whom he had worked for decades, here is what More said right after his emotionally-charged trial:

I verily trust and shall therefore most heartily pray, that though your lordships have now here in earth been judges to my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together. (TMSB 61)

This leads us to the question: how is such a reaction possible? Those of you who have seen the emotional and social scars caused by injustice will appreciate the challenge posed by this question. How is it humanly possible to speak about ‘being merry’, and remaining a friend, with the very people who have betrayed you and have destroyed your life? Is not animosity against injustice … natural?

True, More was convinced that God directs history. True, he was convinced that ‘time tries truth’, and that a wise and brave person can ‘lose his head and have no harm’. But how did he overcome the suffering, the sense of betrayal, the loss?

This question reminds us that knowledge of the truth is very different from living in accord with truth. That, of course, is the whole challenge of integrity: how do we get ourselves to live in harmony with our deepest convictions?

As we all know from experience, conscience alone is not enough to be just. One also needs a strong enough character, an ethos, to live in accord with that conscience. How did More acquire the calm, the courage, the integrity of the skilful captain in the midst of the greatest of storms?

One essential element, More tells us, is freely cultivating in one’s soul – over many years – the loves we have freely chosen as the foundation of that courage. This requires the habit of reflection along with what More calls a ‘right imagination and remembrance’ that precludes ‘murmuring’. The result is a state of mind that even the Stoics saw to be necessary to live true integrity – true oneness in thought, word, and action.

Murmuring or internal complaints are, after all, a result of ‘fond fantasies’ we all tend to create. And realist that he was, More pointed out that murmuring can produce the greatest of harms and can lead to the loss of our interior freedom. The example he uses repeatedly is that of King Saul, whom More seems to present as an archetypal figure that shows what will happen to any good person who does not rule his imagination and remembrance.

Saul, as you know, loved God deeply and was specially created and called and anointed to be the first king of God’s Chosen People. Yet by the end of his life, Saul turned from God, looked to witches for advice, and ended up losing his kingship because of his infidelities. What had happened? As More reflects upon this story, he indicates that it all started with Saul’s interior complaints about the difficulties and uncertainties resulting from the duties of his life. By allowing himself to indulge in these interior lacks of integrity, Saul fell from interior complaint to outward negligence, and from negligence to outright rebellion against his highest love and most cherished principles.

Now, as a point of contrast, consider these words that More spoke to his daughter when she for the third and last time tried to convince him to come out of prison. More said to Margaret:

Nothing can come except what God wills. And I make me very sure that whatsoever that be, even if nothing has ever appeared so bad, it shall indeed be the best. (TMSB 335)

Notice the careful choice of works: ‘I make me very sure’. More knew that he was free, free to live in accord with his deepest convictions – or free to murmur, lose patience, and fall from his once-cherished convictions. It all depends on one’s ethos, one’s character, one’s choice to be consistent in thought and action.

Those astonishing words ‘I make me very sure’, show that More is freely exercising his will to choose his response to adversity, in the light of a conscience formed by his deepest convictions. For More, this choice was an act of loyal friendship with a God whom he did not see, but who spoke clearly in the depth of conscience, but only in ways that invite free response.

Do you see now why Holbein, in order to capture the essence of the man, chose a pensive expression rather than a merry one? Two details within the painting help us.

First, notice the rich green curtain that is drawn back just a bit. What is being revealed here? Why show that white space on the right-hand side? In Holbein’s iconography, it indicates More’s openness to transcendence, to all that is beyond physical sight – which is not the first quality you would imagine in looking at the richness of this well-dressed public official. And More did tell us, by the way, that humour should be the sauce, not the meat, of our conversations.

Second, notice the document in More’s hand. Depicted here is a man of state, with weighty matters literally in hand. Transcendence does not take him away from duty; both are equally present to this man of conscience.

Here is a person whose dying words are ‘I die the King’s good servant, and God’s first’, indicating the profound truth that More lived throughout his life: that no opposition needs to exist between earthly and transcendent duties – proving to us that integrity is possible.

To understand merry Thomas More, one has to consider what a humanly attractive figure he fought to be. The fight was an internal one: against moods, whims, fantasies of imagination; but the external results were abundant: his bright and cheerful home, his life of integrity, his sought-after good judgement, his life as a respected civic leader. The result of that internal fight was a virtuous character that was so attractive that he moved those around him to want to do the good, just as he can move us today.

But what about Lord Acton’s objection, that Thomas More was a political failure – and a rather undignified one at that, making merry quips to menial servants right to the end?

To answer this objection, one must ask: What is the end of politics? This is a classical and Renaissance topic of central importance that we cannot address today, but as Aristotle and Cicero explain, the ends of politics are justice under law and friendship among citizens. That is a view More accepted. Here is just one simple indication.

As a young lawyer, More wrote, mostly translating from Greek sources, two-hundred and eighty-one Latin poems in his effort to reflect upon the entire scope of human needs and aspirations, in his attempt to understand human nature and political life.

One series of seven related poems is entitled, ‘On Two Beggars: One Blind, One Lame’. The original Greek poems represent different reactions to the universal experience of human limitation. Here is one very simple two-line Greek poem from two thousand years ago that More translated, and it is marked by the clear-sightedness that More so admired in the Greeks:

A blind neighbour carries a lame man about; by an artful combination, he borrows eyes and lends feet.

This is a typical, rather matter-of-fact, approach taken by the wisest of the Greek philosophers: they see our condition as it is, and they respond in a constructive way: o.k., we are all either blind or lame, so let us be artful in borrowing and lending. Other versions of this simple poem stress skill or working cooperatively, instead of art, as ways of assisting each other.

But not everyone responds so constructively towards our needy condition. Here is another ancient perspective, translated by More, showing the cynical approach, marked by unhealthy self-pity:

Very sad misfortune overtook two unhappy men and cruelly deprived the one of his eyes, the other of his feet. Their common misery united them.

We have all met this type of sad cynic who reluctantly accepts human limitations and the need for political association.

Now what follows is More’s highly original response to human deficiency and its political implications. Notice the positive tone and the glorious roles he gives to friendship, law, and politics:

There can be nothing more helpful than a loyal friend, who by his own efforts assuages your hurts. Two beggars formed an alliance [a legal term in the Latin, commonly used in treaties for trade or peace] of firm friendship – a blind man and a lame one. The blind man said to the lame one, ‘You must ride upon my shoulders’. [Notice the introduction of dialogue.] The latter answered, ‘You, blind friend, must find your way by means of my eyes’.

There is a magnanimity in this outlook that heightens the status of loyal friendship, free conversation, and political association assisted and strengthened by law. And it is a view that inspires! But where does this perspective come from? We are given clues in the concluding couplet which reveals the deepest motives of fully human action:

The love that unites, shuns the castles of proud kings and rules in the humble hut.

Love is given first place in More’s poem, and humility is given as the condition for good rule.

As this poem indicates, where there is humility and political alliances based on law and love, not only can our radical human insufficiency be assuaged, but the genuine happiness of true friendship can be achieved. Pride, however, is the enemy of happiness, peace, friendship and love: the belief that we ourselves, in our castles of distinction, can be sufficient unto ourselves, that we can be kings or little gods who do not need the support and correction of others. More knew that the danger of conceiving ourselves as little gods is great indeed, because we are created with godlike powers of intellect and will – and therefore will always tend to be proud kings, rather than humble, law-abiding friends.

To bring this to a close, because we are running out of time, consider what recent history has actually shown about the life of Thomas More: in the 1970s, More was exonerated by the Parliament that brought about his death; in 1999 he was voted lawyer of the millennium by the Law Society of his own country; and in 2000 he was declared by Pope John Paul II ‘Patron of Statesmen’ at the request of leaders from around the world.

More’s Renaissance perspective on politics ordered to friendship can help us understand how his merry humour, even on the gallows, could be an appropriate response to the political troubles of his day – a response of cultured civility, human splendour, and culture-changing charity expressing true integrity. When Pope Pius XI declared More’s sainthood in 1935, he summed up the impression of many when he said, ‘What a complete man!’. Or as those petitioning for More to become Patron of Statesmen put it in 1999: ‘the idea that holiness is the fullness of humanity appears, in [Thomas More’s] case, quite tangibly true’. And to use the words of John Paul II in his official Proclamation of 2000: ‘This harmony between the natural and the supernatural is perhaps the element which more than any other defines the personality of this great English statesman: he lived his intense public life with a simple humility marked by good humour, even at the moment of his execution’.

At the end, More bore with good cheer the loss of everything – everything except what was most important: union with the Friend he came to know in the depths of his conscience. For this reason, More was not pessimistic; he did not lose his good humour or his ability to see, and to witness in the most attractive way, to what is true and good – showing the splendour of a good captain who gives not only expert direction to his ship, but also an inspiring example of joy and hope, acting as a lighthouse for his age and for ages to come, no matter how dark the skies or how stormy the seas; a splendid example of true integrity, of one who knew how to live and how to die ‘the king’s good servant, and God’s first’,* inspiring us even today with his courage and good cheer.

Five hundred years later, we have learned, not only that Thomas More could ‘lose his head and have no harm’, but that the integrity of a friend true to conscience can be the greatest legacy that any parent or leader can leave to posterity. That, I suggest, is the greatest legacy of Sir Thomas More.

*That More used ‘and God’s first’, not ‘but God’s first’, see TMSB 355-358.

TMSB refers to A Thomas More Source Book.

Discussion

Discussion

Andrew Hegarty: I should like briefly to make a couple of points.

The first concerns friendship. Authors like C.S. Lewis have written of friendship in the modern world and have argued it is under considerable pressure. There seems to exist plenty of ‘chumminess’ but little real friendship. Some authorities, it has been suggested, frown upon friendship because it constitutes an alternative ‘public opinion’ of its own, with friends serving as a defensive bulwark against attempts to impose certain ways of looking at things. Do you think that the era of More, and of Renaissance ideals, was more open to genuine friendship than our age, and, if so, why?

My second point is about the concept of ethos to which you made reference. I find it interesting that the early Tractarians of the nineteenth century and the men involved in the ‘Oxford movement’ made much of this very notion. They used the Greek word and thought that a man’s ethos conditioned his beliefs. Can you can think of any reasons why the likes of Newman and Froude, in the context of the religious ferment in nineteenth-century Oxford, should have returned to ethos?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: To answer briefly your second question first: ethos is the basic truth about human beings. As for your first, friendship is coming under threat precisely because people have become blind to this basic truth. Was More’s era more open to friendship? Certainly not in the Court culture in which he worked. In his day and ours, we see that power, self-interest, social position and widespread prejudice will dominate over friendship in the absence of that special kind of education which was identified by the best Greek and Renaissance thinkers as being the key to a good culture, healthy politics, and a happy life.

Russell Wilcox: Do you think More’s work as a great Renaissance humanist involved a reaction against ‘medievalism’, and – if it did – was that, in fact, partly responsible for breaking down the type of ethos he claimed he wanted to preserve?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: More clearly states that Thomas Aquinas was ‘the very flower of theology’, so there is not a hint that that type of medieval theology was a problem for him. He does, however, criticise certain kinds of scholasticism and corrupt educational practices. Nevertheless, having the mind that he had, he was constantly looking to draw the best out of existing culture. So I do not think that he would have identified any of the major good elements of medieval culture as a problem.

While More wanted to take the best from the classical world, he recognised that it had been enriched and complemented by medieval theology and philosophy. After all, the great medieval thinkers were already seriously reflecting on, translating many of the classical texts. In fact, some of the saints used Cicero’s great treatises On Duties and On Friendship, and adapted them for their own purposes.

Oliver Bloor : How can a prince make sure he is getting good advice? I wonder also if you could comment on the position of the many people today who are employed in roles which involve receiving payment for advice provided, or for comment on the advice offered by others. More seemingly sidestepped the question of what one should do when one has to dispense advice that runs contrary to the known or anticipated wishes of one’s employers.

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: The prince has to be educated to want good advice just as More saw that he needed to educate his children to want good advice. Erasmus translated and twice dedicated to King Henry VIII Plutarch’s essay How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend: once before Henry’s wars in France and again after the wars had died down. That work helps us to appreciate that good advice is in his best interests.

Some of this education must come from his counsellors, and More played this role for Henry VIII for over fifteen years before men like Cranmer and Cromwell were chosen by the King to do his will. His choice of them seems to have been made in an act of anger after two holy but very indiscrete clergymen publicly shamed him. This history seems to me very instructive. More never publicly shamed Henry and was always very attentive to the danger of doing so. Anyone in a counsellor’s role today knows this from experience.

You could therefore see why an essay like Plutarch’s How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend was essential education for anyone in such a role. It compares language and advice to medicine, likening truth to very powerful medicine, one that is so powerful that it has to be given in the proper doses, not only to the unwell, but also to the healthy. A whole section of the essay is dedicated to the art of candour, explaining that it is possible to lose your closest friend by not respecting his difficulty in accepting truth.

The whole art of diplomacy arises from the deep understanding of human nature that is necessary for good advice, good counselling and good politics. This was the whole cultural project that these Renaissance men had in mind. It is not easy to give good advice or to be a good friend. In some ways, the entire objective of an education is to learn how to do these things.

The two serpents in the picture on the handout are formed in the shape of the symbol of health. Each of these serpents is crowned because reason is king when it comes to diplomacy, friendship and politics. One has to be shrewd and know all the details. That is what makes one a friend or a political expert. A lot of time and effort has to be spent garnering the detailed knowledge needed to be able to administer the truth in a statesmanlike way that will lead one’s country (or friend) forward instead of down to destruction. On the one hand, one might be rash and imprudent, and fail as a counsellor. On the other, one might constantly work not to offer one’s first reaction, always to keep calm, to control one’s emotions and to study things well before giving advice.

Michael Elmer: I should like to know more about Thomas More’s view about the question of silence and prudence. You showed how he was loathe to give his opinion and how repeated attempts were made to force him to take a position. There is a classical dictum that ‘silence gives consent’. Often we may find ourselves in the position of not wanting to comment on something because we are unprepared or lack the necessary expertise, but yet not to speak might suggest that we are ready to go along with that which is asserted by others.

Perhaps some comfort can be taken from the position of More, who – if I remember rightly, and I do not have very detailed knowledge of his life – on a number of occasions might have taken up a position but in fact chose to say nothing at all. There was, for example, the case of Elizabeth Barton, ‘the Nun of Kent’, about which Bishop John Fisher expressed himself while Thomas More – wisely as it turned out – said nothing. Am I right in thinking that in things that did not touch him very closely, he usually took the position of not volunteering a position until actually asked for it?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: This is an issue of prudence: deciding when to speak and when to remain silent. More’s silence was in fact a very shrewd strategy. His position was so clear that he did not have to express it again. After all, More had written nine books before being imprisoned. These books engaged the issues at hand so well that Parliament was on his side. Henry actually had to dismiss Parliament and, instead, he turned to pressure the Convocation of the clergy in order to carry out his plan. More was very successful, and he never directly attacked the King. He was so successful that Henry and Cromwell had to take a considerable risk in arresting him. Sir Thomas. More’s silence – which he used at different points in his career – was always a choice based on informed reflection.

Andrew Hegarty: You have spoken of More being the first to use certain words in English in particular senses. On what basis do you make that judgement?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: That was actually drawn from a very fine M.Phil. thesis from the University of London, which involved a study of More’s first prose works. The woman who wrote the thesis, Susan Carole Weinberg, examined More’s first three works and analysed over two hundred words – going well beyond the work of the Oxford English Dictionary –, and discovered that More was the first to use those words in new ways.

As she points out, More usually would use a word which already had an accepted meaning, but then expanded its use metaphorically or grammatically. For instance, she points out that culture and integrity had physical meanings, i.e., ‘tillage of the soil’ or cultivation of fields for agriculture, and ‘the condition of not being marred or violated’. More extended these words to refer to the human soul. This taking a word and expanding its application to something non-physical is exactly what one would expect from a philosopher and a poet.

Russell Wilcox: The question previously addressed of speaking out and keeping silent is particularly relevant today with the clash we see around us between the culture of life and the culture of death. If one is silent, to what extent is one complicit? One of the scenes which occurs to me in contrast – and from a different moment in history – is when St. Ambrose of Milan confronted the Emperor Theodosius. Ambrose certainly did not remain silent on that occasion but, at the same time, he too gave good counsel. Did More ever write on the subject of complicity in a way which might be useful for us today?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: He gave us his example. While he did not write on that matter explicitly, he did praise Fisher who took on the role of Ambrose…

Andrew Hegarty: Might that not be because a bishop, in virtue of his office, has to do so? More, on the other hand, was a layman.

Prof Gerard Wegemer: This was a theological matter and Bishop Fisher was a member of the Convocation of the clergy. As such, he had a particular duty. As a government leader, More had his own particular duties. Ethical issues arise in every profession and they must be dealt with professionally, often over a long period of time. The statesman does not deal only with what is immediate, but must also think in terms of the span of his life and beyond. In considering More as ‘Patron of Statesmen’, we must take ‘statesman’ in its fullest sense because every profession needs its statesmen.

Russell Wilcox: It seems to me that this is never simply a matter of individual choice. Many people think it is normally the individual taking a decision who is best suited to determine the extent to which he or she is complicit with evil on any given occasion. It does not necessarily follow, however, that others should not – out of friendship and charity – sometimes criticise such a decision. This seems to me a very difficult balance to achieve because it is very easy especially in the modern world – more so than in More’s time – to deceive ourselves into making compromises with a view, as it were, to infiltrating the structures of power. Some persons who have succumbed in this respect may at the end of their lives wonder if they have ever stood up for anything.

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: This is where More is very instructive in the range of good choices he demonstrates. He was an expert in the art of candour: silence, a raised eyebrow, an ironic remark, or some little way to make the person think: any of those from More could be as powerful as direct criticism. This, for me, is why his example is essential for us today. He spent decades recovering the art of candour and the art of statesmanship, and without giving up on principle.

Another aspect of being a statesman which More manifests is the importance of knowing one’s field, profession and country well enough to be able to draw upon accepted truths and principles, and to know where there is agreement or disagreement.

John de Souza : In these recent days we have all witnessed the problems of the Middle East, and one of the things that strike me is how there is lacking on all sides leadership and true statesmanship. Apart from being a statesman and patron of politicians, Thomas More was also a great leader, in the mould of Mandela or Gandhi. These are people who led their people to solutions that did not seem possible at the time.

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: Yes, and it also helps us reflect on what goes into a great leader. The element of trust, for instance, is essential. This is why More said he had a duty to protect his reputation and integrity. After all, a person’s reputation is his public face. It is not easily acquired in a short time and is of the essence of leadership. This brings us back to the question we had about the centrality of ethos for the nineteenth-century Tractarians. Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, points out that the ethos of the speaker is the most important element in persuasion. Does the speaker have a standing for integrity, or is he someone who is shady and not to be trusted?

It is interesting to read the Elizabethan play Sir Thomas More, because it presents a common Londoner’s perspective on More. It was one of admiration and complete trust. This trust had been acquired from the eight to ten years when he had served the people of London as an Undersheriff, helping the poor and the city leaders alike in very practical and tangible ways. It was also acquired because as ‘Young More’, he built upon the sterling reputation of his father, who had long been involved in London and was greatly loved and respected.

Kiko Mitjans: I should like to change the focus of this discussion for a moment to More’s own family. One of the things you mentioned was that, in his letter to the tutor of his children, More stated that education should lead them to ask for advice. In his biography of Margaret Roper, Reynolds says that More did not in fact give them advice at the end of his life. The opinion of Reynolds is that if he had explained his position to his family they would have agreed with him. Do you have anything to say about this?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: A strong objection that is often raised against More is that he was silent publicly and silent even with his own family. Clearly, as persuasive as he was, he could have convinced some of them should he have spoken out. But he knew there was nothing that the members of his family could have done about the situation.

In this he shows us that there are some professional matters about which you just do not speak to other people. It would actually have been an injustice to place the burden on them. More understood history and knew about the behind-the -scenes machinations of Cromwell and Henry VIII to get around the most basic laws of the country and the intent of Parliament. He knew about the pressure that was being placed on the Church in a new way. These were things about which his wife and children could have done nothing. From his perspective it would have been an injustice to have spoken to them about it.

Andrew Hegarty: Could you tell us a little bit about your project for the translating of More’s works into modern English, and, in particular, why you think this is something that must be done?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: One example is the latest modernised edition, coming out in the Fall of 2006, which is A Dialogue Concerning Heresies. It records a conversation between More and a university student who is very confused about all the issues of the age. Very few have read this book and it is an absolute gem when it comes to addressing the types of issues we have been discussing today: How does one get into the mind of another person? How does one lead him or her from certain prejudices and misinformation to a fuller view of the truth? This book presents four days of conversation in which More deals with this young person, even while he is very busy as the King’s Counsellor and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

Another – which I consider his masterpiece – is A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation. This is a three-part discussion in which More speaks with a young relative who agrees with him about all the principles but says that once the Turks come and threaten torture – for which they were famous at that time – he is going to give in. After the three conversations, this person moves from being paralysed by fear to being able to live up to his name, Vincente, from the Latin vincere, ‘to conquer’. His fears are conquered by the help of a Socratic interlocutor, a good friend who gets into the very depths of his opinions and soul to help him out of paralysis and into a state of freedom.

It seems to me that this is what is at stake in recovering Thomas More…

Andrew Hegarty: You mean, in making him readable by modern man?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: Yes, especially for first-time readers. The complete works of any other Renaissance author of More’s status – Spenser, Shakespeare and Sidney, for example – would have been published seven to fifteen years after their lives. A new edition would have been printed, with more commentary, footnotes and studies, in every subsequent generation. For More, a partial publication of his works was undertaken only during the reign of Queen Mary Tudor, twenty years after his death. After that, there was no publication of his corpus until the Complete Works, of which the last volume appeared in 1997.

Andrew Hegarty: You are referring to the Yale edition of his works?

Prof. Gerard Wegemer: Yes. This project took forty years, and involved some twenty scholars from five different countries. The work of recovering More’s vision – which is the vision of statesmanship – is behind our project of getting people to read More’s texts, to think about them and to articulate what they mean. These are the arts of freedom. Human beings will be not be free unless taught how to overcome their emotions, prejudices and shortcomings. Consider again More’s thoughts on the blind man and the lame man.

One must also have regard to the re-education of whole nations. The fact is that no major political philosopher subsequently accepted in Great Britain or America has agreed with More or those thinkers who say that character matters more than institutions. The founding fathers of the United States of America deliberately designed a commercial republic based on self-interest with checks and balances so that reliance on good character would not be required. That approach was, granted, counteracted by the realisation that religion and strong civic associations which develop character were needed. The American Founders from their own experience realised that good character was essential, but they were strongly influenced by John Locke and other social contract theorists. For them it is all about institutions, and checks and balances. More would not deny the need for these, but would stress the importance of education as preparation for citizenship. That, I think, is part of what is at stake in recovering the vision of Thomas More: the classical and Christian vision of the human being, of citizenship, and of true statesmanship.