Published on

7 December 2011

‘Faith in God is not a problem to be solved, but a vital part of the national conversation’ (Benedict XVI)

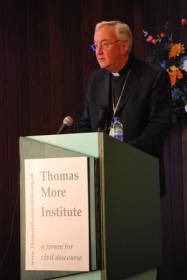

By: Archbishop Vincent Nichols— 2011-2012

ABOUT

The Most Rev. Vincent Nichols has been Archbishop of Westminster and President of the Roman Catholic Bishop's Conference for England and Wales since 2009. The following is the transcript of a lecture given by the Archbishop at the Thomas More Institute on 7 December 2011.

A consistent message and direction often expressed in the actions and teaching of Pope Benedict XVI is the need for an ongoing dialogue between religious faith and the secular mind, based on the role of reason. Indeed, this was central to the appeal he made during the Visit to the UK in September 2010. And many people have remembered that invitation very clearly: ‘I would invite all of you, within your respective spheres of influence, to seek ways of promoting and encouraging dialogue between faith and reason at every level of national life.’ (Westminster Hall 17 Sept 2010)

This is a clear encouragement which must continue to shape our work and mission.

This is not a new initiative in the life of the Church. The words of paragraph 19 of ‘Gaudium et Spes’, spoke of the invitation to faith in these terms, thereby setting the scene for our relationship with those who do not believe in God:

The outstanding feature of human dignity is that human beings have been called to communion with God. From its first moment a human being is invited to encounter God. It exists solely because it is continually kept in being by the love of the God who created it out of love, and it cannot live fully and truly unless it freely acknowledges that love and commits itself to its creator. Many of our contemporaries, however, either completely fail or explicitly refuse to accept this intimate and vital relationship with God, with the result that ‘atheism’ is to be viewed as one of the most serious of contemporary phenomena and merits close consideration. (G & S 19: Tanner)

In other words there is an invitation to be explored together, no matter the different starting points people might take up.

Pope Paul VI, in his solemn closing speech of the Second Vatican Council, pointed to the basis, the key concern, on which such exploration can take place. He said: ‘So, modern humanists, even though you reject transcendence we ask you to recognise our new humanism because we too are cultivators of humanity.’

In the years since the Second Vatican Council, this invitation has lost none of its urgency. Indeed, for many years the exclusion of faith from most public discourse, especially in Europe, has become more insistent, although reactions to the Papal Visit to the UK suggest that new opportunities may be emerging.

Slowly a new place for religious belief in the public square is being marked out, not with a power or desire to impose religious beliefs or their consequences, but with the recognition that a mature and enlightened public square should reflect the beliefs of those who share its space, in dialogue with one another and with secular protagonists, to the enrichment of all. The secular public square should not be faith-blind but faith-sensitive, welcoming and testing reasoned argument. Religious voices should not expect special privilege because they are religious, but nor should they be excluded either. And whilst public authorities will rightly seek to justify their actions by reference to reasons which all can accept, in contributing to public debate religious and faith voices should be free to speak from their traditions as well as to adduce reasons in their support. Encouraging their willing and full participation enriches democracy and at the same time facilitates the necessary dialogue between the world of secular rationality and the world of faith.

Slowly a new place for religious belief in the public square is being marked out, not with a power or desire to impose religious beliefs or their consequences, but with the recognition that a mature and enlightened public square should reflect the beliefs of those who share its space, in dialogue with one another and with secular protagonists, to the enrichment of all. The secular public square should not be faith-blind but faith-sensitive, welcoming and testing reasoned argument. Religious voices should not expect special privilege because they are religious, but nor should they be excluded either. And whilst public authorities will rightly seek to justify their actions by reference to reasons which all can accept, in contributing to public debate religious and faith voices should be free to speak from their traditions as well as to adduce reasons in their support. Encouraging their willing and full participation enriches democracy and at the same time facilitates the necessary dialogue between the world of secular rationality and the world of faith.

What I would like to do this evening, even if briefly, is not so much an exploration of the issues involved in the dialogue between faith and reason as such – and there are plenty of those – but rather an exploration of three points of engagement between the secular world and the world of faith in pursuit of a true and fuller humanity spoken of by Pope Paul VI. This is an aim which, I believe, is shared by many.

The first of these is the deep-seated desire felt by many to live their lives not in isolation but in the context of a network of stable, lasting relationships in which encouragement, companionship and support are to be found.

This search for community, the search for mutual belonging has to compete with another instinct strongly reinforced by many factors today: the instinct to be a free-standing, self-sufficient individual. Worthy as aspects of that aim might be, it is not the whole story and often leaves many people struggling with loneliness. The task of building community has to cope with the pressures of individualism and the fact of isolation.

This struggle was movingly portrayed in the televised account of the emergence of a local choir: the South Oxhey Choir, based in Carpender’s Park in Hertfordshire. Music became the means of overcoming both individualism and isolation. Many living on that estate were isolated from one another for all the reasons well known to you all. Others had to overcome a strong desire to stand in competition with each other, often in a bravado style, rather than cooperate in a choir. The emergence of the choir was dramatic and moving, led by its founder and conductor Gareth Malone. He faced profound reluctance and lack of confidence but persisted. Slowly people came together, accepting common goals and received unexpected encouragement and support. Slowly a community of singers emerged and relationships started to build.

A significant moment arrived when the conductor decided that the choir, for its first really major public performance, was going to go for real depth. He proposed of piece of music – Barber’s Agnus Dei – which was difficult and everybody struggled. It was touch and go. But with a lot of individual coaching the choir succeeded and the final performance was met with acclaim.

Gareth explained what he wanted. He wanted the choir to experience real depth: depth of sound, depth of harmony and depth of emotion. And he did this in the context of religious music.

The task of building community is a forum in which the religious and the secular meet. This can happen on many different fronts and settings. But the search for depth is one in which the role of religious faith can become truly crucial, for faith is that response to the revelation of the true depth of our humanity and therefore a revelation of the deepest dimensions of our experience and, indeed, of our nature. Once a group of people, sharing experiences of one sort or another – be it hill-walking, art, bird-watching or music – begin to ponder on the depth of their shared interest, then the invitation to wonder, the surge of awe, will come to the fore. Then they are entering into the preambles of religious faith, into its foothills, and careful accompaniment can indeed lead the search into the realms of the gifts of revelation.

It was pointed out to me the other day that the Catholic Church is one of the few places in our society – in fact the person said it was the only place, and I wonder if that is true – where people from all different classes and strata in society actually sit next to one another and assume both an equality and mutual identity. This is surely so because the members of that community share an explicit faith. Faith provides its depth. Sunday by Sunday, people come together, from all walks of life, and know that they are bound to each other in Christ, in the Church, and one fundamental struggle: to live as his disciples.

This, perhaps, points to one of the most creative things that the gift of religious faith brings to our society today. In our faith we explore that which is truly universal while not letting go of, nor losing, our particularity and we do so in community.

The same can be said of music: in singing I become part of a greater whole without losing the distinctiveness of my voice. In my Christian faith the gift is deeper: I am taken up into the Eternal Word of God, the binding force of all created things, yet I do not cease to be me. In the universality of this truth, from which nothing is excluded, I am tutored in my sense of belonging to one, creating and loving Father. I learn a universal perspective without which life is essentially fragmentary and, in all probability, solely competitive and/or oppressive. In that universal perspective I learn to see others as my brothers and sisters; to see that their burdens are related to me, and mine to them; to know that spiritual realities bind us together and offer us mutual support through prayer; to recognise a common destiny in the fullness of life which only the graciousness of God can bestow upon us all.

At the same time, this experience of Christian faith does not rob me, or us, of our particularity. We are created and loved as unique individuals. We are called to walk a particular pilgrimage in life, with our own purpose or vocation. We are called to recognise the distinctiveness of the gifts of others, even the gifts of other religions and other faiths. We rejoice in the gift of faith in the unique Incarnate Word of God, yet we also recognise the seeds of that same Word in many faith-inspired words and actions of others very different from ourselves.

In the work of building community, I am suggesting, the gift of religious faith, and particularly the gift of Christian faith, is the ground and framework for exploring the reality of the diversity of human living within the context of its fundamental unity. And there are few tasks more urgent in our complex world today. Give up on respect for diversity, and we are impoverished and eventually become either dominators or dominated. Give up on the search for universality and we lose confidence in any bonds of unity between us, in any substance in a shared humanity and we splinter into a thousand fragmented and isolated groups or even individuals.

One role of faith in God today, in our public conversation, is to offer service in the task of forming community, a community that is both cohesive and open, a community that reaches for universality and respects particularity. That is a vital contribution.

The second point of engagement between the world of faith in God and our secular world today is connected to this, too. It is the search for meaning in the life of every person: that instinct to reject the proposal that life has no coherence, no lasting purpose and is no more that a series of experiences, leading to final annihilation when the course is run. As Pope John Paul said in ‘Fides et Ratio’:

It is the nature of the human being to seek the truth. This search looks not only to the attainment of truths which are partial, empirical or scientific; nor is it only in individual acts of decision-making that people seek the true good. Their search looks towards an ulterior truth which would explain the meaning of life. And it is therefore a search which can reach its end only in reaching the absolute. (para 33)

This search is closely connected to the first point of engagement because, as many philosophers and thinkers have highlighted, the central issue is whether a human being can be the sole and independent source of their own meaning.

The contribution of our Christian faith is clear: the gift that we bring is that of a revealed truth. Here, as a gift, is the light by which every person can make sense of themselves and their lives, by which they can find their way and, just as importantly, by which they are themselves ‘enlightened by grace’.

Pope Benedict expressed this conviction clearly in his recent address to the German Parliament when he described the human person as ‘one who did not create himself’ and therefore, not enjoying ‘self-creating freedom.’

He used these descriptions not in order to take a negative stance on the quest for meaning but in order to open up a pathway of reflection on the quest for meaning which may indeed be attractive to many today.

First of all he highlighted our present increasing awareness of the demands of the natural environment. Increasingly we have to pay attention to the inter-relatedness and fragility of so many facets of the ecological systems of the world around us. This ecology demands our understanding and respect. In some ways we have to learn to obey the demands of the environment and not imagine that it is ours to do with as we please. Of course we have to use nature creatively, but when we exploit it wrongly we compound the difficulties we face.

The Pope’s point is that the human person too has an ecology which has to be understood, respected and obeyed if we are not to compound our human problems and create crises in our humanity when we think we are doing no more than taking what is our due. He said: ‘Man is intellect and will but he is also nature and his will is rightly ordered if he respects his nature, listens to it and accepts himself for who he is, as one who did not create himself.’ This is the pathway to true human development.

What exactly is meant by this ‘human environment’, this human ecology?

Perhaps I could suggest the following as three aspects of our human ecology which are more fully explored in our Christian tradition and can be brought to our dialogue with our secular world.

The first is the truth that we are both relational and individual beings. This is the ecology in which we flourish. In some ways this has already been explored in what I have said about community. But it goes further, too, for this tension between our relational characteristics and our individuality also lie at the root of many ethical questions: do I behave so as to satisfy my deepest individuality – ‘doing my own thing’ – or do I bear in mind most of all the effect on others of my actions. The collapse of either pole is a corruption of our ecology. The struggle to manage this dilemma is dependent on a clear sense that there are principles and norms of behaviour which bind us together, which we share because of our nature, which have an objective quality to them. When we search for those norms, through the light of revelation and the use of reason, then we are better equipped to find the way of action which most sustains our true freedom and growth together.

The second truth is that we are both spiritual and corporeal: every human person is an essential unity of spiritual soul and body, such that the human person is both ‘embodied spirit’ and ‘spiritualised body’. This is an essential part of our ecology. In many ways this may seem obvious, but there are voices today that deny totally the reality of the spiritual, insisting that experiences of beauty and love, sooner or later, will be fully explained by physical actions and reactions within the human body. Other voices minimise the relationship between body and spirit to such an extent that the bodily reality, and the satisfaction of its needs, is all that really matters. And the converse is true, too: there are some who so minimise the requirements of our bodily nature that the spiritual – or relational – reality alone gives meaning and validity to their actions. But we are inseparably body and soul, and the quest for truth must always keep this relationship in balance if our ecology is to be preserved.

Then there is a third truth: we exist both in the present and are historical beings. Yes, we live in the present and we must search for our meaning and purpose in the present circumstances. But we are also carriers and inheritors of a tradition, of a past and that, too, is a crucial part of our being and of our flourishing. It does not serve the health of our environment if we cut ourselves off from our heritage.

This, of course, applies in many different ways. Ignorance of our history means that we are more likely to repeat its mistakes. But acknowledgment of it means that we have to learn humility and repentance. The rejection of the wisdom and foundations of the past – as with the place of Christianity in Western culture – does not give us unrestricted freedom to do what we like now, but puts us in danger of building on shifting sands which have not been tested for their stability or their capacity to bear the weight of our culture.

In Westminster Hall, Pope Benedict spoke of challenges facing democratic societies ‘if the moral principles underpinning the democratic process are themselves determined by nothing more solid than social consensus.’ Democracies need to retain the sense of their place in history and the inheritance on which they are built. In G.K.Chesterton’s famous phrase, there is also a ‘democracy of the dead’ and the voices of the past are important contributors to our search for health today.

The gift of Christianity is that these tensions are resolved in the person of Jesus and in relationship with him we learn best the wisdom of heart and action that leads us to true freedom.

The personhood of Jesus, which is that of God the Son, is unique, precisely in virtue of its relations to the person of God the Father and to the person of God the Holy Spirit. Jesus reveals to us that the one God is a communion of persons; that divine being is relational. Jesus alone, within the unity of his divine person, holds together the divine nature and his individual human nature. He is the synthesis of the whole and the particular, which we all seek.

Then Jesus is also the one in whom the fullness of the Holy Spirit resides in a human body. He holds together the spiritual and the physical. His work of eternal salvation is achieved within human flesh. His victory over death is completed in the resurrection of his body. His continuing presence among us in the sacraments of the Church is both spiritual and material. In him we glimpse, and are given a share, in the resolution of this tension which will be fully achieved in the final coming together of all things.

Jesus is also the one in whom the story of history is completed. We hold him to be the fulfilment of all the promises of God, drawing together in himself the long story of salvation history. Yet this fulfilment is also a transformation. The story is not simply brought to an ending, but rather to an entirely new phase in which the balance between promise and realisation is radically shifted. Now we know that in him the promise is fulfilled. It is achieved. For our part we wait in hope for the moment when our sharing in that victory, already achieved, will come about. In Christ the relationship between our past, our present and our future is resolved.

It is the privileged task of the Church to be the messenger of this new hope. This is the gift we bring to the dialogue between faith and secular culture and it is a gift that does indeed serve to ‘cultivate humanity’ as Pope Paul so finely stated. Our task, then, is one of unfolding this gift in a manner in which it may be received. It is a task of skilful teaching and many voices contribute to that task, particularly, I might add, the voice of the priest.

I say this because we are often reminded that the true authenticity of the proclamation of the Gospel is its fruitfulness in evoking self-sacrificing love for others. And such love is at the heart of the vocation to the priesthood, seen particularly vividly in the gift of celibacy. When such total love for the Lord is seen to be the basis of a priestly vocation then the words and teaching of that priest have a particular resonance and power in the hearts of his hearers.

This brings me to the third and last point of engagement between the world of faith and our secular culture which can be fruitful today. It is the work of caritas, or practical care for the poor and those in need.

There is no doubt of the immense generosity that is so often seen in the response of the people of this country to those in need. Disaster emergency appeals always bring that generosity to the fore. This year’s ‘Children in Need’ appeal raised record amounts of money despite the hard economic times. Generosity is writ large in people’s hearts.

What does the vision of our Christian faith bring to this reality?

May I illustrate the answer to that question by referring to a most sensitive area: the response to the spread of Aids, not least in Africa. This is how Pope Benedict pinpointed the specific contribution made by our faith to this terrible suffering:

The solution must have two elements: firstly, bringing out the human dimension of sexuality, that is to say a spiritual and human renewal that would bring with it a new way of behaving towards others; and secondly, true friendship offered above all to those who are suffering, a willingness to make sacrifices and to practice self-denial, to be alongside the suffering. So these are the factors that help and that lead to real progress: our twofold effort to renew humanity inwardly, to give spiritual and human strength for proper conduct towards our bodies and those of others, and then this capacity to suffer with those who are suffering, to remain present in situations of trial. (17 March 2009)

These are clear and powerful words. Their message is vitally important and well understood by many. He reminds us that poverty – of every kind – can never be reduced to a technical problem and it can never be resolved by technical responses alone. There is always a profoundly human dimension to poverty. This we know. Our sympathy is aroused by the plight of those who are suffering – the testimony heard last week from victims of human trafficking. Our response, too, must focus on that human reality seeking to offer not simply funding for technical solutions but human love, accompaniment and solidarity.

This is the contribution that we can make to the work of ‘caritas’ – that it never loses its human face, for we know that this face is the face of Christ. In ‘caritas’ we see that the Gospel is not only informative but also performative – it makes things happen and is life changing. (cf Spes Salvi para 2)

There is much more I could say: about Catholic Social Teaching and its relevance to many aspects of public debate today; about research which indicates how people involved in communities of faith respond more generously and more selflessly than most to appeals for help; about the relationship between many freedoms in society and the fundamental freedom of religious belief and expression in practice of that belief. But time has run out.

I thank you for your attention and I hope that these remarks and the discussion to follow will add a little light to the ways in which our faith can be an important contributor to public debate and to the growth in health and well-being of our society.