Published on

31 May 2007

Faith and Hope in the Fight for Freedom: Stories from the Frontlines of Human Rights Advocacy

By: Ben Rogers— 2006-2007

ABOUT

Ben Rogers is Advocacy Officer for South Asia at Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) Seminar on Wednesday 31 May 2007

The title of my talk is Faith and Hope in the Fight for Freedom. Before I go into some of the countries and situations I should like to bring to your attention, I want to set the scene, in a perhaps slightly unorthodox way, by quoting from Bob Dylan some words, taken from his song ‘Blowing in the Wind’, which pose some fundamental questions for us in this room but also for society at large:

The title of my talk is Faith and Hope in the Fight for Freedom. Before I go into some of the countries and situations I should like to bring to your attention, I want to set the scene, in a perhaps slightly unorthodox way, by quoting from Bob Dylan some words, taken from his song ‘Blowing in the Wind’, which pose some fundamental questions for us in this room but also for society at large:

How many years can some people exist

before they are allowed to be free?

How many times can a man turn his head

and pretend that he just doesn’t see?

How many ears must one man have

before he can hear people cry?

How many deaths would it take till he knows

that too many people have died?

I do not know if you are aware that persecution of Christians – by no means the only issue I want to address this evening, but the major focus of the work of Christian Solidarity Worldwide – is a major and growing phenomenon around the world. It is believed that over two hundred million Christians around the world, in over sixty countries, face persecution, discrimination and restrictions of one form or another. They face threats from all sides, from extremists of other religions, from authoritarian governments, from particular elements in society – especially Islamic fundamentalists in places like Pakistan. Christians are currently under pressure not only in Pakistan but also in Indonesia, by Hindu nationalism in India, by what can only be described as ‘militant Buddhism’ (a contradiction in terms) in Sri Lanka, and by authoritarian regimes in China, North Korea, Vietnam and Burma – the latter of which will be the major focus of my remarks this evening. CSW is a Christian organisation, and we therefore believe we have a particular responsibility to speak up for Christians facing persecution because, if we do not, few others will. We believe, however, that our advocacy should not end there, and that we should take up the call to be a voice for all voiceless people who are suffering oppression and injustice.

I have personal experience of Burma, East Timor, and partially of China – I lived in Hong Kong for few years and travelled into China many times –, but I work also on Sri Lanka and Pakistan. I will not attempt to cover all these countries here. I am going to focus briefly on Pakistan and then predominantly on Burma. However, if you have questions on the other countries mentioned – Sri Lanka, East Timor, China – I am happy to address those in the discussion afterwards.

Pakistan is a country where religious minorities, women and also many ordinary Muslims are suffering because of the rise of extremism. Perhaps the greatest cause of injustice in Pakistan is a law introduced by the dictator who ruled Pakistan through most of the 1970s and 1980s, General Zia-ul-Haq. This is known as the ‘Blasphemy Law’, according to which the witness of one man alone – usually a Muslim man, but it does not have to be so – accusing a person of having said something blasphemous against the Prophet Mohammed or of having desecrated the Koran is sufficient for the accused to be arrested by the police, imprisoned and put on trial. The ultimate penalty for blasphemy against the Prophet is the death sentence. Nobody has actually been executed by the state, but, in the eyes of the extremists, persons accused of this are marked for life, so that even if acquitted they remain targets for extremists and have to spend the rest of their lives in hiding.

The law is frequently used against religious minorities, and particularly Christians, but it is also often used by Muslims against each other, often for aims completely unrelated to religious matters. For instance, a shopkeeper who wants to achieve a monopoly quickly may accuse a rival of having said something blasphemous in order to have him imprisoned. As far as I am aware, in all known blasphemy cases the charges are completely fabricated. I do not know of anybody who has actually said something blasphemous or deliberately desecrated the Koran, although there are instances in which people have been charged because they have accidentally damaged a Koran. That leads us to the heart of the injustice of that law: it is completely lacking in any regard for intent, and it fails also to weight the burden of proof – the accusation of one man alone is enough, and that has brought about huge injustice in the country.

In addition to the injustice that the Blasphemy Law itself causes, it has also fostered a climate of intolerance and of extremism.

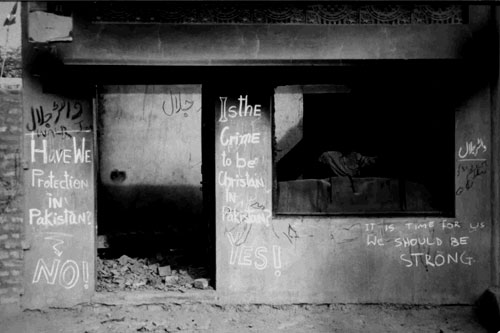

‘Is it a crime to be a Christian?’ – this was written on the wall of a burnt-out building of a village called Shantinagar, which was the target of a major attack against the Christian community a few years ago. There had been subsequent attacks on other Christian areas, and right now there is a community of five hundred Christians in a town called Charsadda in the North-West Frontier Province who were recently given ten days to convert to Islam with a deadline on 17 May. They were warned that, if they did not convert, they would face death. I have been in constant contact with our sources on the ground who have been with this community, and on 17 May – the day of the deadline – I phoned our contact in Pakistan to find out what the latest was and he was absolutely desperate, saying that the Pakistani authorities were not taking this issue seriously enough and that they had simply provided one policeman at the church. He pleaded with me to raise this issue with the British Foreign Office, the United States State Department, the European Union and other governments, so I immediately went to the ‘phone.

Something I should like to mention here – and this may be something to develop in our discussion later – is the huge difference of approach between the United States State Department and the British Foreign Office. It is astonishing how dependent these issues are in the Foreign Office upon attitudes of individual desk officers or diplomats either in the country concerned or in London. I could not believe my ears when the Pakistan officer at the British Foreign Office used this expression, ‘There is nothing we can do; this is an internal matter for Pakistan and we cannot interfere in the internal affairs of another country’. I said to the officer that all we were asking for was that the British High Commissioner in Islamabad might encourage the Pakistani authorities to provide proper security for the Christian community in this town. She replied that there was nothing they could do, but that she would forward the communication to Islamabad for their information. ‘Five hundred people may be killed tomorrow for your information’, I thought, but I restrained myself f rom adding this aloud. This highlights one of the problems we face in dealing with our own government. The State Department, on the contrary, has an office for ‘International Religious Freedom’ and my contact already knew about the situation and assured that they were monitoring it closely and they were trying to do what they could.

rom adding this aloud. This highlights one of the problems we face in dealing with our own government. The State Department, on the contrary, has an office for ‘International Religious Freedom’ and my contact already knew about the situation and assured that they were monitoring it closely and they were trying to do what they could.

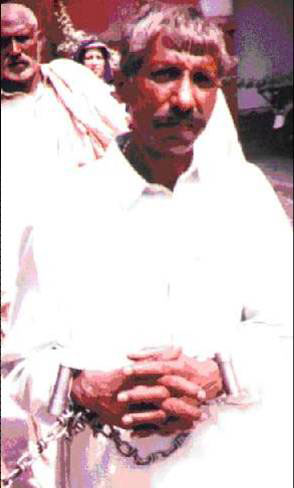

This is by way of an introduction to the situation in Pakistan. I mentioned that many of the people who have been charged with blasphemy, even when acquitted, have had to go into hiding.

This man, Aslam Masih, has been released from prison but the extremists are quite literally hunting him down, and he has to move from one house to another to stay safe. Another problem that women generally and, in particular, women and young girls in the religious minorities have to face in Pakistan is that of sexual violence. I am sad to say that the seven-year old girl that you see here

w as brutally raped and tortured a couple of years ago. I met her after that attack and she was completely traumatised. Her mother said that she had thought she was dead, although eventually she did survive. Another twelve-year old girl was recently kidnapped, told to convert to Islam, and when she refused she was moved from house to house to be gang-raped and each time she was told: ‘If you convert to Islam, we will stop doing this’. She finally managed to escape. Her story is not unusual in Pakistan.

as brutally raped and tortured a couple of years ago. I met her after that attack and she was completely traumatised. Her mother said that she had thought she was dead, although eventually she did survive. Another twelve-year old girl was recently kidnapped, told to convert to Islam, and when she refused she was moved from house to house to be gang-raped and each time she was told: ‘If you convert to Islam, we will stop doing this’. She finally managed to escape. Her story is not unusual in Pakistan.

How do we deal with some of these issues? Besides calling the Foreign Office or the State Department, we try to be pro-active. We took a Member of Parliament with us a couple of years ago to Islamabad and we had high-level meetings, including one with the Prime Minister of Pakistan. We will continue to raise these issues directly with the Pakistani government as well as with our own government. In the case of a country like Pakistan, where a flourishing civil society exists, it is possible to develop a dialogue with the government and to raise these issues.

I turn now to Burma which is very different from Pakistan in many ways, not least because it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to develop a meaningful dialogue with the regime. While in Pakistan there are opportunities to influence the government and to discuss crucial issues, in Burma it is much more difficult. I describe it as a nation with fifty million people living in a giant prison without walls, ruled b y an illegal military regime. I say ‘illegal’ because it held elections in 1990 and they were overwhelmingly won by the National League for Democracy, led by the Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, and yet the regime retains its grip on power. Most of those who were elected in 1990 are now either in prison or in exile. Aung San Suu Kyi is in her twelfth year of house arrest, renewed just a few days ago. There are more than 1,200 political prisoners, and the highest number of forcibly conscripted child soldiers in the world. It is an Orwellian regime, whose extraordinary propaganda is emitted also in English – quite astonishingly, as one might rather expect them to prefer hiding it from the world. This was the ‘warm greeting’ that I received when I went to Rangoon last year:

y an illegal military regime. I say ‘illegal’ because it held elections in 1990 and they were overwhelmingly won by the National League for Democracy, led by the Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, and yet the regime retains its grip on power. Most of those who were elected in 1990 are now either in prison or in exile. Aung San Suu Kyi is in her twelfth year of house arrest, renewed just a few days ago. There are more than 1,200 political prisoners, and the highest number of forcibly conscripted child soldiers in the world. It is an Orwellian regime, whose extraordinary propaganda is emitted also in English – quite astonishingly, as one might rather expect them to prefer hiding it from the world. This was the ‘warm greeting’ that I received when I went to Rangoon last year:

‘Tatmadaw (which is the name of the army) and the people, cooperate to crush all those harming the union’. Aung San Suu Kyi, as I mentioned, remains under house arrest – the world’s only Nobel Laureate currently in detention.

Despite all of that, there are many signs of courageous dissent and people who, in various ways, show resistance to the regime. One example is a wonderful group of comedians in Mandalay, known as the ‘Moustache Brothers’,

Despite all of that, there are many signs of courageous dissent and people who, in various ways, show resistance to the regime. One example is a wonderful group of comedians in Mandalay, known as the ‘Moustache Brothers’,

who are no longer allowed to perform publicly in Burmese, but they are still permitted to perform in English in their own homes – perhaps as a token effort suggesting to foreigners that there is a certain degree of freedom of speech. I went along to a performance, and it was both highly entertaining and very inspiring. Several of them have spent long periods of time in jail.

In relation to the forced conscription of child soldiers,

this is a boy who at the age of 11 was standing at a bus stop in Rangoon en route to visiting his aunt. He was picked up by a truck-load of soldiers who grabbed him and told him he had to join the arm y. When I met him three years later he had managed to escape. I asked him if he was given a choice whether to join the army or not, and his answer was simply that his choice was either to join the army or to go to jail. He did finally escape, and he said that the treatment in the Burmese army was horrendous. The words he left me with were: ‘Life in the Burma army is like hell’. He escaped in the knowledge that if he was caught, he would probably be killed, but he said, ‘I did not want to live anymore’. Thankfully he did survive the escape and he is now in safety in Thailand.

y. When I met him three years later he had managed to escape. I asked him if he was given a choice whether to join the army or not, and his answer was simply that his choice was either to join the army or to go to jail. He did finally escape, and he said that the treatment in the Burmese army was horrendous. The words he left me with were: ‘Life in the Burma army is like hell’. He escaped in the knowledge that if he was caught, he would probably be killed, but he said, ‘I did not want to live anymore’. Thankfully he did survive the escape and he is now in safety in Thailand.

Burma is a predominantly Buddhist nation, and it is a nation where ordinary people of different religions live in peace and in harmony with each other. Traditionally there have not been problems in the relations between people of different religious backgrounds. However, it is a nation where the military regime uses Buddhism as a political tool to suppress others, and their distorted use of Buddhism is surely far from consistent with what I know of authentic Buddhist teaching. It is essentially a fascist regime, one of whose slogans is, ‘One race, one language, one religion’ – the ‘one religion’ being Buddhism. It is not just intrinsically intolerant  of other religions , but also of Buddhists who do not subscribe to its own interpretation of Buddhism. Many Buddhist monks are currently in jail.

of other religions , but also of Buddhists who do not subscribe to its own interpretation of Buddhism. Many Buddhist monks are currently in jail.

Christians and Muslims, however, are particularly targeted. I published a report a couple of months ago called Carrying the Cross which deals with these issues. The situation in the country varies from region to region. One could go to Rangoon, see churches open and functioning, and might think there is little, if any, problem. But even in Rangoon, under the surface, Christians do face problems. They face restrictions on their activities, and discrimination. It is very difficult for Christians to get promotion in government services. Admittedly, the climate they face in urban areas, although subtly insidious, is not violent. In some of the ethnic areas, however, particularly in the Chin and the Karen areas, they do face explicit and often violent religious persecution, resulting in the destruction of churches and crosses, in forced conversions and coercive acts such as being forced to build Buddhist pagodas in the place of crosses

This is the Catholic cathedral in Rangoon,

and this one of the many Baptist churches in Rangoon

The regime did not seem to like my report, and that was not unexpected in itself, but what was perhaps surprising was how much attention they paid to it. For about two weeks, The New Light of Myanmar (the State-run newspaper) published every day full-page statements condemning the report and Christian Solidarity Worldwide and refuting my allegations. Several of my friends from Burma confirmed that the government did pay a lot of attention to it. We are somehow grateful to them, for if they had not acted as publicity agents many people in Burma would not have become aware of these efforts.

Let me turn now, in the final section of what I should like to share with you, to what is perhaps the most important element of the situation in Burma, and possibly the most forgotten. On top of political prisoners, suppression of democracy and use of child soldiers, there is what I believe amounts to a form of genocide taking place against many ethnic groups. There are too many ethnic groups in Burma to list individually here. Broadly speaking,

however, the Karen, the Mon and the Shan are the major groups in the eastern part of Burma; the Chin on the western border with India; the Kachin on the northern border with China; the Arakan and the Rohingya, which are mainly Muslim people, on the border with Bangladesh. I have been to almost all of those borders, apart from that with Bangladesh, and these people are facing horrendous crimes against humanity: destruction of their villages, forced labour, and the use of rape and killing.

however, the Karen, the Mon and the Shan are the major groups in the eastern part of Burma; the Chin on the western border with India; the Kachin on the northern border with China; the Arakan and the Rohingya, which are mainly Muslim people, on the border with Bangladesh. I have been to almost all of those borders, apart from that with Bangladesh, and these people are facing horrendous crimes against humanity: destruction of their villages, forced labour, and the use of rape and killing.

Many of the Karen people are Christian. Here we have a picture of a church in the jungle

This is a picture of what was a church

which has been burnt down and destroyed.

I have also been twice to the Chin people on the India-Burma border. (I am pleased to see here this evening Dr. Desmond Kelly who has a long history of involvement with the Chin and is far more versed in their story than I.) The area of the Chin people is one of the poorest areas in Burma, lacking investment, health-care and infrastructure. They face persecution on three grounds: religion, ethnicity and politics. They are mainly Christians and feel very forgotten. They told us, ‘We used to pray that someone would come to us, and we used to weep when no-one came’. Children from Chin Christian families have been taken away from their villages to Buddhist monasteries and forced to become monks and nuns at a distance from their families.

The Karen and Shan in Eastern Burma face what are certainly in my view crimes against humanity. Theirs is a case that should be investigated as an instance of genocide. Since 1996 over 3,000 villages have been destroyed, and over a million people internally displaced. In Karen State right now the worst offensive in a decade is taking place. In the last year alone, over 27,000 people have been forced from their homes. Their villages have been burnt down and often surrounded with landmines to prevent the inhabitants from returning. Civilians are shot at blank point range. Recently we had reports of a nine-year old girl and of a deaf man shot dead, and of a woman raped and murdered.

This is how I usually get into Burma

This is how I usually get into Burma

Out of my seventeen visits to Burma, only one has been legal. Most of the time I go across the border from Thailand into the jungle without a visa or a passport, because this is the only way to see the reality of what is happening to the most forgotten and most vulnerable people. When we do go, we find scenes like this

This was a village that had been attacked and burnt down just few weeks before our arrival. And this is the same village after they had built it up again

Certain communities whose villages had been attacked were in some ways luckier than others. If they lived next to the border, they could cross it when they were attacked and nobody was killed – they lost their homes, but not their lives. The communities deeper inside  Karen State, and those in other ethnic states that have no safe place to which they can run, are even more vulnerable.

Karen State, and those in other ethnic states that have no safe place to which they can run, are even more vulnerable.

Describing the intentions of the regime, a Burmese army general said a few years ago that if the government had its

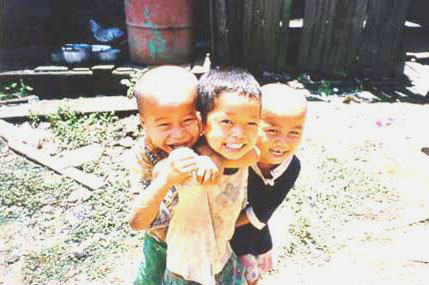

way, all the Karen would be dead in ten years. At that point, he suggested, if you wished to see a Karen you would have to go to a museum in Rangoon. That is the fate that could await children like this on

way, all the Karen would be dead in ten years. At that point, he suggested, if you wished to see a Karen you would have to go to a museum in Rangoon. That is the fate that could await children like this on

The photograph

is of a boy we met on a journey into Shan State. He had seen his parents killed in front of him and his village burnt down while he himself had been taken away for forced labour. As he told his story, he looked in my eyes and he said words I will never forget, words that motivate my work in Burma: ‘Please tell the world to put pressure on the military regime to stop killing its people; please tell the world not to forget us’. Here again are people used as human minesweepers,

who had to walk across minefields to clear them for the military. They lost limbs in the process, while others were killed.

in the process, while others were killed.

It is very difficult for the children we have met to describe what they have experienced, but sometimes it is possible for them to draw something and that may even be therapeutic for them . The results, however, are horrifying. This is a drawing by a 10 year-old child

We see a baby being crushed to death in a rice pounder, a woman being killed, and another woman being held captive. These are the kinds of crimes that the children today have to witness in various part of Burma.

I would like to pass on through some other images, without saying much about them, hoping that they will stay with you after my words have gone

I would like to pass on through some other images, without saying much about them, hoping that they will stay with you after my words have gone

When we travel, it is very important to obtain first-hand testimonies. This picture

was taken in a camp for internally displaced people in the jungle where we were interviewing many victims of the most recent offensives. The man had been captured and severely tortured. He had been beaten so badly that he had lost his sight. He was forced to stand for a whole day and the soldiers poured red ants all over him.

been beaten so badly that he had lost his sight. He was forced to stand for a whole day and the soldiers poured red ants all over him.

Finally, I should like to say a few words about the Kachin people. The Kachin are an ethnic group I came to know more recently. They are certainly as forgotten as the Chin, if not more so . One of the reasons they are particularly forgotten is that they have in place a ceasefire agreement with the regime, so that they are not engaged in armed resistance. On the positive side is the absence of armed conflict. Therefore, the most grotesque crimes – destruction of villages, and displacement of thousands of people – are not taking place in their region. Some more subtle or individual crimes, however, such as rape, forced labour, religious discrimination and religious persecutions certainly are taking place. The people are very nervous of speaking out because of the ceasefire they have in place. In  some ways their situation is even worse than that of others. Things are, however, starting to change, and I have been working with them to try to be a voice for them on the outside to raise awareness. Kachin State, bordering on China, is beautiful

some ways their situation is even worse than that of others. Things are, however, starting to change, and I have been working with them to try to be a voice for them on the outside to raise awareness. Kachin State, bordering on China, is beautiful

I met with the Kachin Women’s Association several times and they have been particularly active on the issue of human trafficking. Kachin women are sold into China either for prostitution or as wives, and some have been trafficked as far away as the border between North Korea a nd China.

nd China.

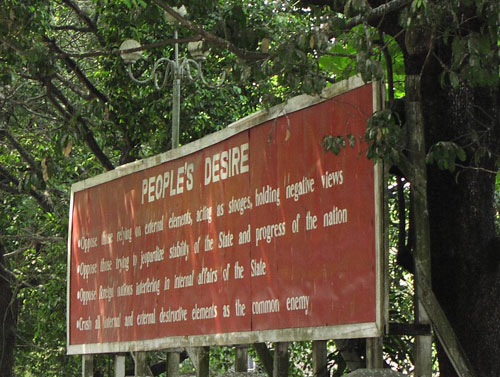

Another piece of the bizarre propaganda of the regime is what they call ‘the People’s desire’

which goes like this: ‘oppose those relying on external elements, acting as drudges, holding negative views; oppose those trying to jeopardise the stability of the state and the progress of the nation; oppose foreign nations interfering in the internal affairs of the state;’ – they were not counting our Foreign Office there, given its line on Pakistan! – ‘crush all internal or external disruptive elements as the common enemy’.

I would suggest that the people’s real desire is somewhat different. They desire an end to scenes like this

I would suggest that the people’s real desire is somewhat different. They desire an end to scenes like this

a village after it had been attacked, with inhabitants watching the burning of their village following the flight of the perpetrators. The people’s desire is for peace and for this kind of thing

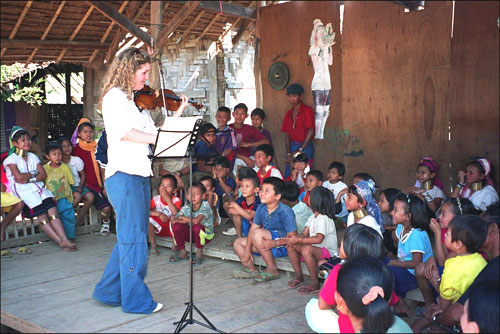

here you see my sister, a musician, who came with me on a trip last year, playing her violin, an instrument many had never heard before. This shows the incredible capacity of music to communicate beyond words and languages.

These people desire more of that. Their desire can, in fact, be summed up in the words of a Christian Chin Pastor who said: ‘Please let the world know: we want freedom, freedom, just freedom. Freedom to speak, freedom to worship, freedom to praise God, freedom to work, freedom to learn, freedom to write. Just freedom’.

The people’s desire is to receive an answer to a question posed in this photograph

The picture was taken in a village of internally displaced people whose situation was dire. I remember walking around and seeing people dying of treatable diseases, of malnutrition, and of malaria. It was a desperate state of affairs, and I was feeling rather depressed by it. Then I turned a corner and walked past a little bamboo hut. Something inside caught my eye – a banner hanging on the wall which poses a simple question for all of us who have the privilege of living in freedom: ‘Are you for democracy or dictatorship?’.

If, as I assume, we are for democracy, what can we do? We at Christian Solidarity Worldwide have a motto: ‘Pray, protest and provide’. Keep Burma and all the nations of the world that are not free in your prayers and hold this image

If, as I assume, we are for democracy, what can we do? We at Christian Solidarity Worldwide have a motto: ‘Pray, protest and provide’. Keep Burma and all the nations of the world that are not free in your prayers and hold this image

in your heart as you do so. ‘Protest’ can take many forms, and we can explore how that might work later. And ‘provide’ in whatever way you feel led to do so.

Let me conclude with two quotations that sum up the messages that I have tried to convey tonight. First of all, this photograph

this photograph

shows a Karenni relief worker who on 10 April 2007 was captured by the Burma army while delivering humanitarian aid to his people. He was captured, held for several days, interrogated, brutally tortured and then, I am sad to say, executed. The organisation he worked with, the Free Burma Rangers, said this about him – and I think it sums up our ambitions in Christian Solidarity Worldwide:

He was a wonderful man who smiled at everything; he is missed by us all. He was killed doing what he believed in: bringing help to people under oppression. His death is tragic, but not in vain. He has made a mark of love and service that made a difference in the lives of those he helped, and in all of our lives’. Our ambition is that people may be able to say of us that we try to make a ‘mark of love and service.

Thomas à Kempis in his Imitation of Christ wrote these words:

Those who love stay awake when duty calls, and wake up from sleep when someone needs help. Those who love keep burning, no matter what, like a lighted torch. Those who love take on anything, complete goals, bring plans to fruition. But those who do not love faint and lie down on the job.

I believe that those of us who live in the free world cannot afford to ‘faint and lie down on the job’. We should remember the words of William Wilberforce, very much in our thoughts this year, who said in introducing legislation to end the slave trade: ‘We can no longer plead ignorance, we cannot turn aside’.